Women, science, and celluloid

Hidden Figures, one of the most compelling and inspirational films of 2016, recounts the heretofore untold story of African-American women working for a NASA task force group in the early 1960s.

The film is a rarity in many ways. Historically, the number of real-life biographical films about significant pioneering women scientists has been infinitesimally small. I find that intriguing given the fact that there have long been women scientist characters in sci-fi and horror-film narratives. Early horror-film prototypes include Anna Lee as a medical surgeon working alongside a deranged scientist played by Boris Karloff in The Man Who Lived Again (1936) and Janice Logan in Dr. Cyclops (1940) as a biologist confronting a crazed doctor using radium deposits to shrink living creatures.

Reflecting on more recent times, the arrival of digitalized computer-generated filmmaking has seen women scientists as obligatory presences in untold numbers of sci-fi screen adventures. In my favorite sci-fi film of 2016, Arrival, Amy Adams portrayed a gifted linguist who must interpret and decipher messages from extraterrestrial spacecraft that have landed on Earth. Arrival points out just how introspective and provocative a screenplay with a sophisticated female scientist can be in sci-fi filmmaking.

The classics

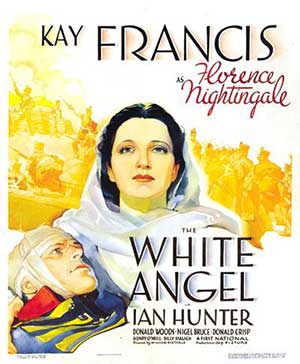

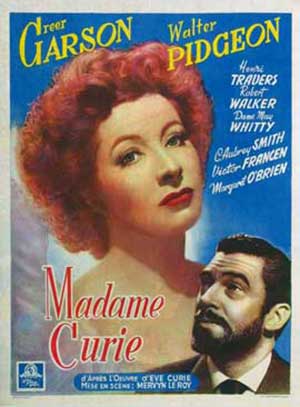

I must give Hollywood its due before returning to Hidden Figures by recognizing two classic American films about female scientists: The White Angel (1936) about nursing and health care pioneer Florence Nightingale, and Madame Curie (1943), the story of two-time Nobel Laureate, Marie Curie. It is worth noting that these movies were socio-cultural products of the era in which they were made.

I must give Hollywood its due before returning to Hidden Figures by recognizing two classic American films about female scientists: The White Angel (1936) about nursing and health care pioneer Florence Nightingale, and Madame Curie (1943), the story of two-time Nobel Laureate, Marie Curie. It is worth noting that these movies were socio-cultural products of the era in which they were made.

The White Angel is a good example of the many 1930s biographical films Warner Bros. produced during the Great Depression. It’s a tale of dogged determination. As its plot unfolds, Florence Nightingale (Kay Francis) lives with her British upper-class parents who strongly object to their daughter’s desire to become a hospital nurse. Undeterred, Florence leaves home and enrolls at the Institution of Kaiserwerth in Dusseldorf, Germany, where she takes on a challenging course in medical training. On completion she returns home to England only to discover no one will hire her; the medical field was considered strictly male territory.

Aware of the horrific medical conditions being experienced by Crimean War soldiers, Nightingale and a couple dozen nurse recruits travel to a hospital outpost in Scutari, Turkey. Nightingale soon gains a reputation as a compassionate caretaker who walks through the wards at night with a lamp to check on her patients — “the angel in white.” Adversity sets in when her work is soundly opposed by hospital director Dr. Hunt (Donald Crisp) who replaces her as lead nurse with a woman whom Nightingale had rejected as an unqualified recruit. Though the media at the time lauded her work in the Crimea, government and military officials refused to recognize Nightingale’s achievements. The White Angel concludes with Queen Victoria presenting her with a brooch as a token of appreciation. Its inscription reads: “Blessed Are the Merciful.”

At the time of its release in 1936, the film was recognized as an inspiring account of determination and courage in the face of adversity. New York Times film critic Frank Nugent praised the movie for its honest and graphic depiction of Nightingale’s “gallant crusade on behalf of nursing.” In his review, he referred to the power figures who opposed Nightingale “as shrewd personifications of conservative stand-pat medical and army men.” (June 25, 1936).

Noble and Nobel

The screen treatment of Marie Curie at MGM also contained a dramatic mixture of adversity and success. Released in the midst of WWII, Madame Curie was regarded as a historical biography designed to inspire. The plot opens with Polish-born Marie Sklodowska (Greer Garson), poor, malnourished, and studying physics at the Sorbonne in Paris. One day she faints in class, prompting her tutor (Albert Bassermann) to invite her to an evening gathering at his home. There she meets Pierre Curie (Walter Pidgeon), a physicist whose interests are single-mindedly focused on his lab work. Although Pierre has told his young male assistant that women are a danger to science, he sees in Marie someone as gifted and fully committed as he is. He offers her a place in his lab, and his affection for her grows. Marie and Pierre marry in 1895.

The screen treatment of Marie Curie at MGM also contained a dramatic mixture of adversity and success. Released in the midst of WWII, Madame Curie was regarded as a historical biography designed to inspire. The plot opens with Polish-born Marie Sklodowska (Greer Garson), poor, malnourished, and studying physics at the Sorbonne in Paris. One day she faints in class, prompting her tutor (Albert Bassermann) to invite her to an evening gathering at his home. There she meets Pierre Curie (Walter Pidgeon), a physicist whose interests are single-mindedly focused on his lab work. Although Pierre has told his young male assistant that women are a danger to science, he sees in Marie someone as gifted and fully committed as he is. He offers her a place in his lab, and his affection for her grows. Marie and Pierre marry in 1895.

Throughout her marriage, Marie continues to concentrate on her doctoral thesis about radioactive energy that emanates from an element discovered in pitchblende rock. Skeptical, the physics department denies Marie and Pierre research funding and the two are relegated to temporary lab space in a small shed nearby. At one point Marie suffers badly burned hands during a mishap in the laboratory, but with a large supply of pitchblende rock, the two scientists eventually come upon a method of crystallization that results in the production of pure radium. For their discovery, Marie and Pierre Curie are awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize for physics. Three years later Marie is devastated when Pierre is killed by a horse-drawn wagon on a Paris street. Still, she dutifully carries on her scientific research and is rewarded with a second Nobel Prize in 1911, this one for chemistry.

On its release in 1943, war-era filmgoers and critics widely hailed Madame Curie for its inspirational depiction of the couple’s patient devotion that led to the discovery of radium and further scientific innovations.

Blazing a trail

Adversity-met-with-patience-and-devotion also drives the thematic core of Hidden Figures. The plot follows three African-American women who provided mathematical calculations and flight trajectory data for the NASA space task group as it prepared to launch astronaut John Glenn into orbit. The early-1960s time frame brings the space race together, via television news coverage, with the concurrent civil rights movement. These two historical moments coalesce to add a subtextual dimension to Hidden Figures’ revelations about the plight of brilliant women of color in overcoming gender and race discrimination.

Adversity-met-with-patience-and-devotion also drives the thematic core of Hidden Figures. The plot follows three African-American women who provided mathematical calculations and flight trajectory data for the NASA space task group as it prepared to launch astronaut John Glenn into orbit. The early-1960s time frame brings the space race together, via television news coverage, with the concurrent civil rights movement. These two historical moments coalesce to add a subtextual dimension to Hidden Figures’ revelations about the plight of brilliant women of color in overcoming gender and race discrimination.

The source material for the screenplay is Margot Lee Shetterly’s historical bestseller Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race (William Morrow/HarperCollins, 2016). The book traces the careers of black women who worked for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) located in Hampton, Va., at the Langley Research Center.

Shetterly grew up in Hampton, and as a child she knew some of the women whose stories are “revealed” in her book. Highly educated African-American female mathematicians, most with degrees from all-black colleges, found federal and war-related employment after 1941, the year that President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law Executive Order 8802 that banned racial discrimination in hiring. Further, World War II had reduced the number of men available for government work.

In the ’40s and ’50s, hundreds of smart black women moved to Hampton seeking employment at NACA. Those who were hired worked in a segregated office at Langley’s West Area Computing Center — designated by a sign that read “Colored Computers.” Laboriously, the women analyzed mathematical data on manually operated Friden adding machines, earning less than their male counterparts. In relocating to the small town of Hampton, the women often faced difficulties in securing housing, not to mention finding adequate transportation (buses were segregated) and proper schooling for their children.

On screen

The screenplay for Hidden Figures capsulizes the story of the West Area “Colored Computers” by centering the plot on three principal characters: Katherine G. Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), a physicist and mathematician; Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer), a mathematician and leading figure in the computer unit offices; and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monae), a mathematician with aspirations of becoming the first black female space engineer. At work, the three are depicted bravely tolerating the discriminatory Jim Crow conditions at Langley. Outside the workplace, they are shown bonding and supporting one another through social interaction.

The screenplay for Hidden Figures capsulizes the story of the West Area “Colored Computers” by centering the plot on three principal characters: Katherine G. Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), a physicist and mathematician; Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer), a mathematician and leading figure in the computer unit offices; and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monae), a mathematician with aspirations of becoming the first black female space engineer. At work, the three are depicted bravely tolerating the discriminatory Jim Crow conditions at Langley. Outside the workplace, they are shown bonding and supporting one another through social interaction.

The dramatic arcs of Hidden Figures develop in Dorothy Vaughan’s quest to become the supervisor of the West Area Computer unit; in Mary Jackson’s goal of becoming a space engineer, which requires additional scientific study only available to her through evening classes at Hampton’s segregated high school; and in Katherine G. Johnson’s singular expertise at calculating flight trajectories — skills that land her in the all-white, all-male offices of NASA’s Space Task group.

Johnson must contend with unrelenting opposition, sexism, and racism from her primary co-worker (played by Jim Parsons). She also faces the seemingly impossible task of winning over the unit’s director (Kevin Costner). Personal indignities ensue: A coffee pot appears marked “colored.” With no toilet available to her in the task group building, Johnson must run, in high heels and sometimes pouring rain, a half-mile to the West Area “colored toilets.” Without complaint, Johnson endures. Her expertise proves essential for Glenn’s launch into orbit aboard Mercury Capsule Friendship 7.

This tripartite rendering of the stories of Vaughan, Jackson, and Johnson presents the three as ideal representatives of the intelligence and devotion of the “black women mathematicians who helped win the space race” as Shetterly’s book puts it. And in that story, it also can be seen as a symbolic statement for all who harbor hopes of the American dream and who work unrelentingly to achieve it, no matter the impediments

On Jan. 24, 2017, Shetterly visited Ann Arbor and spoke to overflow crowds on the University of Michigan campus. As he introduced her, President Mark Schlissel referred to Hidden Figures as one of the “best and most important films” to have come along in years. Appropriately, Shetterly received an extended standing ovation as she shared the news she received that same day — that the screen version of her book had received three Oscar nominations, including Best Picture.

Rolf Lorenz - 1983

Hi Frank, many years have passed until I am finally again able to read a column about FILM from you. Will you be around A² at the end of August?

Kind regards,

Rolf

Reply

Downs Herold - '63 '65 '68

Nice to see you’re still sharing your great film knowledge.

Reply

Sandy Gale - BGS - 1981, MA - Telecommunications

Dear Professor Beaver:

(Can never call my mentors by their first names!)

This is Sandy Helble. You gave me so much confidence

and encouragement undergrad and grad.

Learned to love film even more in your classes. I still

have my copy of “On Film” … loved Film History.

Wonderful to read your insights.

Great memories of Moviolas and broken splices.

Things have changed.

Plan to see this movie this week.

Very Best To You and Yours,

Sandy

Reply