Forest for the trees

In the 1860s, when Michigan soldiers were fighting the Confederates in the American south, the lower peninsula’s forests still stretched in a magnificent green blanket from the Thumb to the Straits of Mackinac — white pines and hardwoods five feet around at the ground and soaring to heights of 200 feet.

By the time those Union soldiers were grandfathers, the forests had been stripped and sold off. Much of the northern lower peninsula had been turned into a wasteland of stumps and slash, waiting for someone to lead the work of starting the forests over.

That figure arrived in Ann Arbor in 1903. He was Filibert Roth. Twenty years later he would be recognized as one of America’s great foresters, and known among hundreds of U-M forestry students as “Daddy” Roth.

Son of the German forest

Born in 1858 to a German father and a Swiss mother, Roth spent his early years roaming German forests. When he was 12 years old, his family emigrated to Wisconsin, where he was apprenticed to a shoemaker. When he was 18 his father was mysteriously murdered. To relieve his family of one mouth to feed, he struck off for the West on his own, working his way from one sawmill and cattle ranch to another.

In his mid-20s he returned to Wisconsin to teach at a country school and prepare himself to qualify for college training. He met and married another teacher, then enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he paid his way through school by working as a curator at the University Museum.

There a professor of botany, Volney Spalding, spotted Roth’s first-class mind and temperament, and coaxed him into the study of trees. Before long, mostly through self-education, Roth had a BA and enough graduate training that he was one of the country’s leading authorities on the new field called “timber physics” — the study of the structure of trees and wood.

Professor and forester

With Spalding’s help, Roth landed top jobs in forest management at the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and the Interior. As chief of the new Forestry Division at Interior’s General Land Office, he was charged with reforming the management of federal forests, long overrun by inefficiency and corruption. He designed a thorough revision of forestry practices, but it ran into snarls of red tape. So he was ready when academe reached out once more.

Roth spent two years at Cornell, then was recruited back to Michigan, where the regents had established a full-fledged Department of Forestry. They named Roth to run it. The state of Michigan gave him a second job — state forester, with a mandate to restore 34,000 acres of cut-over land around Higgins and Houghton Lakes.

He began a career-long campaign to bring responsible forest management not just to Michigan’s depleted woodlands but to forests across the country, public and private. He urged federal over state control of disputed woodlands, fearing that states would cede authority back to the private lumber companies responsible for the ravages of clear-cutting in the 1800s.

But Roth’s main impact on forestry grew from his impact on the generation of foresters whom he trained.

Into the woods

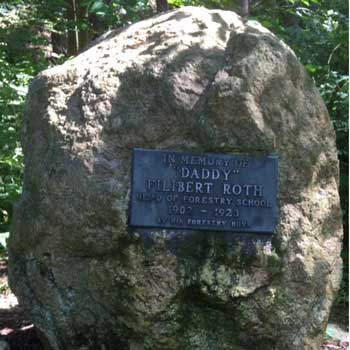

This boulder at Saginaw Forest celebrates “Daddy’s” contributions to U-M and the environment. (Image: James Tobin.)

As an instructor he was superb — an expert’s expert, yet always down to earth and able to unpack the difficulties of understanding a forest.

According to one of Roth’s students, “He had an uncanny ability to make difficult and complex propositions appear simple . . . ‘Now,’ he would say in that kindly way of his, ‘just what is it you are trying to find out?’ He could shuck the husk off a problem and expose the kernel of it in the shortest time. He cut through reams of devious, intricate reasoning in a manner apparently intuitive . . . Where most of us fumble or grope he traveled easily and saw clearly.”

For the lumber barons responsible for what he called “scavenger logging,” Roth had only scorn. But with his “boys,” he was warm, friendly, and supportive. He hand-wrote long letters to encourage them to attend Michigan, and when they were ready to graduate, he wrote equally long letters of support, extolling them to prospective employers.

Early in his career he had to speak up for university training against old-school critics of book-learned woodsmen. But he also believed deeply that the best training in forestry happened in the forests.

Week after week, he sent his “boys” packing on foot out to Saginaw Woods, an 80-acre reserve at Ann Arbor’s western edge. On this farmed-out plot — donated to U-M by Regent Arthur Hill (namesake of Hill Auditorium) — Roth’s students improved the soil and planted some 40 species of trees to see which would fare best.

“Those Michigan men are good,” the president of the Society of American Foresters once remarked. “They may not know more forestry, but they do more.”

“Life is too full of good things”

Most important, perhaps, Roth’s students were inspired to imitate his character.

Long after his death, one of them remembered an especially rough outing with “Daddy” into the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York.

The black flies were swarming; the trail was bad; and when they finally pitched camp for the night, pessimistic talk about their plans for forestry careers was spreading among the students.

Roth listened for a while, then said softly: “I don’t know how it will be with you boys, but as far as I am concerned, I have never felt that I had time to stop to make money — life is too full of good things.”

“The manner, the personal magnetism, not the words, went deep,” the student remembered. “There was no more grumbling, and every man around that campfire remained in forestry.”

In 1912, Roth accepted an offer to become head of the new Department of Forestry at Cornell. He was expected to take many Michigan students with him. A somber farewell banquet was staged by the University’s Forestry Club.

But Roth’s colleagues and supporters throughout the state were determined to keep him in Michigan. When the regents promised more funding — not for Roth, but for his department — he sent Cornell his regrets.

“I am here sto stay,” he wrote in the Michigan Forester, “and I propose to devote the rest of my time to building up our school; your school . . . Let us all join hands in this enterprise and make Michigan what it should be — the great forestry school of the nation.”

In 1923 he stepped down, saying he felt his strength was waning. “I never had any use for a ‘has-been’ in a big place he cannot fill,” he said.

William Greeley, chief of the U.S. Forest Service, wrote Roth a personal letter.

“The greatest monument to your work,” Greeley said, “will be the wonderful crowd of foresters whom you have launched into the profession and the spirit of usefulness and zeal which they have carried from you into their professional duties.”

Roth died two years later, in 1925. His Department of Forestry evolved into what is now U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability. When the University established a summer training camp for forestry students in the Upper Peninsula (first near Munising, then re-situated to Golden Lake, near Iron River), it was named for Roth. And a new forest crown stretches across large swaths of northern Michigan and the Midwest. These were “Daddy” Roth’s longest lasting legacies.

Sources included Samuel T. Dana, “Filibert Roth — Master Teacher” Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review (February 1955); Dow V. Baxter, “Filibert Roth,” Science (April 1926); and the Michigan Daily.

(Editor’s note: This story has been updated since its original posting Oct. 20, 2017.)

Kenneth Rogers - 1978

How in the world can you pen an article about Filibert Roth and make no mention of the Michigan Field School that bore his name on the western shore of Golden Lake in Iron River, Michigan. Many of us SNR Forestry and Wildlife Graduates spent a summer studying there as part of our SNR degree programs.

Reply

Stephen Kunselman - 1986

I believe I was one of the last to graduate in 1986 from U-M School of Natural Resources with a BSNR and major in forestry (the BS Forestry degree had been removed just years prior). I was inducted into Xi Sigma Pi, the National Honor Society of Forest Resource Management. And I attended spring semester in 1984 at Camp Filibert Roth, the former CCC camp in the UP, which unfortunately the U-M sold off in the early 90’s – it was by far the greatest educational experience I ever had in my 8 years of college. The experiences I had in Michigan forests while a U-M student with great Professor’s like Burton Barnes, who wrote the book “Michigan Trees”, are extremely reminiscent of those described in this article by U-M forestry students nearly 100 years ago. It is a great honor for me to be a part of the history that Filibert Roth created at U-M.

Reply

MICHAEL BAILEY - 1973

My 1973 BS was in Natural Resource Management as my original goal of a BS in Wildlife Management was being phased out in the early 1970’s. I also believe your excellent article missed an opportunity be not noting Camp Filbert Roth and all the great instructors and administrators of CFR. One such man was Dr. Archibald Cowan, or Arch as some of us knew him. Arch was a very gifted man in natural resource knowledge, especially wildlife, and in the techniques and desire to pass this on to his students. As the wildlife professors left Michigan in the early 70’s Arch became mine and many other students unofficial “advisor” and mentor. He spent many years as an instructor and top administrator at CFR and helped guide students in many fields of natural resource management. I will forever be in his debt as his mentorship, friendship and knowledge were directly responsible for my ability to have an enjoyable and rewarding career in wildlife management.

Reply

Carl Jordan - 1958

I spent the summer of 1955 at camp Filbert Roth. For me, it was the most meaningful experience of all my academic career. I wanted to learn about the outdoors, and that was what the camp did for me.

Carl Jordan

Professor Emeritus

Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia

Athens, Georgia

Reply

Robert Farmer - BSF 1953, MSF 1958, PhD 1961

It is good to document in this way the School’s heritage which I think is sometimes lost in today’s buzz words, change and complexity. Good that the above folks note the importance of Camp Filibert Roth. I hope students’ experience at UMBS will have the impact that Camp Filbert Roth had on us. I experienced both.

Reply

Brian McKenzie - BSF 1984

While my time at Michigan came long after Filibert Roth, his name was still prominent and his accomplishments not lost. I spent the summer of 1982 at Forestry Camp at CFR and the summer of 1983 there as a Research assistant for Dr Witter. My time at forestry camp was undoubtedly the pinnacle of my education. It was a sad time to witness the school undergo a review as I was completing my studies and this review essentially eliminated the long standing forestry program. I have great memories of my time at the U and Camp Filibert Roth.

Reply