One is the loneliest number

The life of the professional author is in central ways a lonely one. I don’t mean to cry crocodile tears on a writer’s account, but the work is done in isolation and almost always without an immediate response. Even if a book gets published, it’s likely to take a good while to appear, and by then the writer — if he or she be scrupulous — is engaged with yet another project. There’s no reaction — whether great praise, great dispraise, or (the most likely) benign neglect — that’s anything other than a gravitational side-drag upon the forward motion of the work at hand. To receive a fan letter or a good review is, of course, a welcome thing but almost always irrelevant to the labor of writing itself.

I mean by this that the point and counterpoint that we consider the norm of human interaction is denied the writer. Communication — as good a term as any for what most artists hope to achieve — is a two-way street. Every act of artistic creation is a dialogue, not monologue; each stimulus provokes, or should, a measurable response. An actor or musician will know, almost on the instant, how the audience feels about her or his performance; an athlete knows at the close of a race or game if it’s been won or lost. Yet a writer requires months and maybe years to earn a positive or negative reaction.

And when the reaction does come, it is rarely germane to the craft. The fan who writes a letter will tell you her Aunt Sadie also went to Machu Pichu once; the critic who complains that your stallion is a gelding will be riding his own hobby-horse; the friend who feels compelled to praise your work will have read it quickly, more out of duty than desire. The dedicated reader is a rara avis indeed…

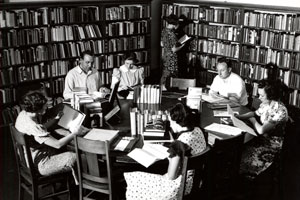

The Hopwood Room has long served as a hub for creative writers on campus. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

In a writing workshop, however, this is not the case. When your work comes under scrutiny, you have witnesses who pay close attention and offer up their thoughts. If only because these fellow participants hope to have, when their turn comes, an attentive reading, they will provide one for you, and hard on the heels of creation.

There’s risk attached to this; most original work takes time to gestate fully, and too many contradictory suggestions may create confusion. Some young writers cringe at critiques and prefer to work in privacy. But it’s almost always useful to be told, while engaged in a project, that this is a path to follow and that a line to cut. If you trust your colleagues (and no workshop can succeed without trust) you leave the session with advice that helps you power forward through the draft. This too is a comparative rarity and will not be repeated in the “professional” years.

We all are selective as readers. We know on the instant, paging through a magazine or newspaper if we want to read an article; we know rapidly, when standing in a bookstore or in front of a library shelf, which book to pick up and take home. There’s no contractual expectation, further, that we must finish what we start; as an editor once told me, when talking of the “slush pile,” “I’m always looking for a chance to stop reading.” The first line or first page or first chapter may be sufficient to tell us we don’t need to continue; quite often the experience of reading is a distracted one, and attention wanders until we close the book.But in a writing workshop that’s not how we behave. Again, if only because all students hope their own work will be carefully attended to, they’re honor-bound to scrutinize the work of others at the table. You read all the way to the end of the story or chapter under discussion, even if it disappoints you, and formulate a response. In a culture where the skills of composition are largely taken for granted or devalued, it’s inspiriting to share a space with those who share your belief in the craft and practice it together. That “lonely life” described above gets put on hold.

My idea of a successful workshop — with, say, a dozen students — is one that produces 12 separate styles, 12 voices achieved and distinct. My idea of a failed class is one where each participant comes out repeating the instructor and imitating as closely as possible the style of the head of the table. It’s the task of all teachers of writing to recognize and help enable an aspirant author’s particular gift — her subject, his ear for dialogue, her diction, his themes. What we hope to hone is each individual’s talent and word-choice: what sets them apart from the rest.

To have a close-knit group of colleagues give careful consideration to your work is a luxury few practitioners have, and one they mourn when it’s gone. (It’s part of the reason “writers’ groups” or “readers’ circles” have proliferated lately; many graduates of MFA programs try to keep their old circle unbroken and to stay in touch.) But it’s why I’m always moved, at semester’s start, by the gathering of apprentice authors at a table. Once they were total strangers; soon, they’ll know each other well. Their work once had only one reader; soon it will be shared. Earlier they labored in “silence, exile, and cunning” (James Joyce’s great phrase for the writer’s condition); soon, they will have colleagues in the craft.

I don’t mean to overstate this, but there’s something quasi-sacred about the chance to devote oneself, wholly and uninterruptedly, to the creation of a work of art. And to do so in a company whose values are the same. I revere this opportunity and try to impart that sense of reverence to others in the room. More often than not, we agree.

Barbara Stark-Nemon - 1971, 1977

The single most important writing experience I had as a student at Michigan came through learning close reading in classes taught by Alice Ann Bloom, an Instructor in the English Department in the early 1970s. Reading and writing about the work of D.H. Lawrence and William Faulkner in the intimate group of those classes honed my skills as a novelist. The depth of insight and critique, and the trust cultivated in those small seminars informed my participation in a writer’s group to this day. In post-student days, my two years spent at the Bear River Writers Conference with Elizabeth Kostova, cemented my skills as a member of a critique group.

Reply

Nancy Cameron - 80, MA and attended undergrad 74

Although I was not in the English program, I had an older next door neighbor in Grand Rapids who won the Hopwood Award. Not sure what year, but her maiden name was Margaret Carlson. She must have been part of the circle of students like above. She went onto teach @ Wisconsin State in Eau Claire. I hear from her every Christmas via letter.

Reply

Karen Wolff - 1976, 1979

As a retiree who took up fiction writing, I cannot agree with you more about the importance of a writing group. Not only have I made great friends, but they have helped me to write my first novel which which will be published soon.

Reply

Susan Siris Wexler - 1951

In 1951 I took an MA in Creative Writing with the very dear and hugely accomplished Roy Cowden. Frank O’Hara was in the class. To earn an MA we were required to write a work of fiction, nonfiction, drama, or poetry. Frank’s choice was a book of poetry. Our seminar, which I believe was weekly, was organized around the study of excerpts of manuscripts that Prof. Cowden had photographed when studying at the British Museum. I remember examining pages from Hardy and I believe Keats where we were asked to defend our analysis of why the author made changes…crossed out, added, and so on. We also shared pages of what we ourselves were writing. I think there were about fifteen of us. It was one of the most memorable experiences of my life.

Reply

Ethel Larsen - 1972

Although I am a Michigan grad, my Michigan writers’ workshop happened when I was still in high school, via a three-week summer seminar in 1967 taught by H. C. Brashers. Heady stuff for a 17 year old. And what a thrill to have my writing appear in Dr. Brashers’ resulting creative writing textbook.

Reply

David Epstein - 1983

I had a creative writing workshop with Cassandra Laity, and another, in poetry, with Richard Tillinghast. I was young and full of myself, and admired a few fellow writers and disdained most. What I admired most was when writers were open and willing to show their vulnerabily. I recall, in particular, a classmate who signed his name without vowels, Crstphr, and a woman who wrote about permanent damage to one arm after being “passed up” at a UM football game. The Tillinghast poetry workshop was fantastic: good poets, a school for analysis, and superb guests. William Stafford, in particular. I also remember professor Tillinghast being adamant that po-em is a two syllable word. I tried to tease him on this point in a written self-assessment that I ended by saying one thing I had learned is that “poetry” is a two-syllable word. If you want a wormhole love story to fall into, look up Cassandra Laity.

Reply