Movie shorts: Tradition and the 2013 Oscars

Something truly wonderful has been coming to movie theaters over the past few years: program screenings of Oscar-nominated shorts. Programs at Ann Arbor’s Michigan Theater in February were so well attended that holdovers occurred over a three-week period, right up to the day of the Academy Awards telecast. Filmgoers were enthralled. Outbursts of applause often erupted after individual films in the three categories—animation, documentary, and live-action. Animation shorts ranged in length from 4-15 minutes, documentaries ran about 40 minutes, and live-action entries ran between 18-25 minutes. Winners from last year’s competition introduced the 2013 contenders, pointing out, emphatically, just how much filmmakers can achieve artistically in a short film and how much these artists can say about the human experience. To see these films is to affirm those claims.

I was struck by how many of the filmmakers carry on the traditions of older, classic short films. For example this year’s animation winner, Paperman (Disney), is an imaginative exercise that combines non-naturalistic, hand-drawn, and computer-generated black-and-white imagery.

The film’s dramatic arc is born of urgency: A lonely New York office worker spots a beautiful woman on a train platform after a sheet of paper blows away and sticks to her face. The paper blows back—with a red lipstick smudge on it—the only color in the film. The woman disappears and the lonely man thinks he’ll never see this beauty again. But soon after, he notices her in an office building across from his. What ensues is an effort to reconnect, first by folding paper airplanes and aiming them unsuccessfully at her open window. The use of paper as a woo-back ploy continues until the determined office clerk’s stack of work has completely disappeared. But the missing sheets of paper magically resurface as the clerk leaves for home—crescendoing into a happy, fluttering ending. Though it’s only six-and-a-half minutes in length, Paperman is rich in feelings of loneliness and longing.

A day at the beach

The use of objects for storytelling and commentary has long been a technique in short animated films. A classic example is the Zagreb (Yugoslavia) School of Animation short Ersatz (1961). Ersatz (The Substitute) was drawn by Dusan Vukotic and became the first foreign-language film to win an Oscar in a non-foreign film category. Using a Paul Klee-like drawing style to create a humorous and urbane theme, Vukotic tells the story of a pudgy man during a day at the beach. His only possession is an air gun that he uses to create objects by inflating geometric scraps of colored paper: a beach ball, a raft, fishing gear, and most significantly, a lovely bikini-clad female companion. When she appears at first glance too skinny for his tastes, he deflates her and blows up another dreamgirl whose proportions better suit his preferences. From another scrap of paper a shark is inflated so that an heroic rescue can be effected. When a he-man appears on water skis and competes for the female creation’s affection, the air-gun man pulls her plug and she deflates back into a paper scrap. Our protagonist meets an ironic demise when, leaving the beach, his air-filled automobile strikes a rusty nail and his self-created world shatters into colored paper wedges. Ersatz can be taken as a satirical statement of the modern world’s obsession with and easy acquisition of material objects. It also cleverly illustrates the potential for self-destruction through mankind’s genius for invention.

Paperman and Ersatz are the works of animators who see the genre’s potential for witty, satiric, abstract, and graphic expression. This has been the clear direction of the short animated film over the last half century. You can see the trend in the upcoming Ann Arbor Film Festival (March 19-24) at the Michigan Theater where animation entries will be on prominent display.

One to one

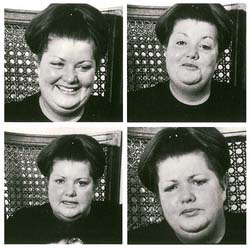

Betty Tells Her Story (New Day Films)

Another longstanding element of independent film shorts has been the psychological exploration of individual personae on screen. In the 1940s experimental, subjective self-studies emerged in films by Maya Deren (Meshes of the Afternoon, 1943), Curtis Harrington (Fragments of Seeking, 1946), and Kenneth Anger (Fireworks, 1947). These films came to be called psychodramas because of their combination of reality, dream, and fantasy elements.

Psychological exploration of individual personality in short films also made its way into more traditional documentary forms. Betty Tells Her Story (1972) is one example.

In this 20-minute film a woman recounts the story of a dress she bought for a ball and what she thought it would mean to her appearance and self-esteem. When the dress inexplicably disappears, she buys another. But the new dress doesn’t mean the same for her. After she finishes telling the story, the filmmaker, Liane Brandon, asks Betty to repeat her story. In the second version—each shown in a closeup shot of Betty speaking into the camera—Betty’s expressions and mood change perceptively. The film viewer senses that Betty is experiencing deeper feelings and meaning about the significance of the dress for herself as a woman. Betty Tells Her Story has earned status as a major breakthrough documentary short that explored personal psychology through film.

This year’s Oscar-winning documentary short, Inocente, is named for a 15-year old Latina in Southern California who has shown precocious talent as an abstract artist. This beautiful and moving film is essentially a psychological inquiry into a short life filled with despair and depression, as well as dreams and fantasies of a better future.

Inocente (Fine Films) recieved the 2013 Oscar for best documentary short.

The primary exploratory technique used by filmmakers Sean and Andrea Fix Fine, as in Betty Tells Her Story, is direct camera address, with Inocente speaking at intervals throughout the film. The direct address begins as Inocente applies bold makeup to mask her insecurities and shameful secrets at a school she attends alongside much wealthier students. Between her candid conversations with the camera and us (including thoughts of suicide shared with her mother) Inocente is shown turning canvases into fantastical color creations—many that are themed as reflections of her personal life.

Inocente is a compelling psychodrama study and it is, in the end, an uplifting portrait of a brave, spirited young woman. From her tearful appearance on the 2013 Oscar stage with the winning filmmakers it was evident just how much the documentary had been an unveiling of Inocente’s fragile, psychological self.

Tradition and accessibility

Shawn Christensen’s Curfew was awarded the 2013 Oscar for best live-action short. In many ways this was the most traditional and audience accessible of the five live-action contenders. Christensen, who also wrote the screenplay, portrays suicidal Richie who is asked by his desperate, estranged sister to babysit her young daughter, Sophia. Reluctantly, Richie agrees to do so with specific guidelines, including curfew hours spelled out by the sassy, tart-mouthed Sophia: “Mother says you’re passive-aggressive.” Richie replies, “What’s that?”

In the course of their evening on the town, the two reluctantly but slowly begin to embrace one another. Curfew wins us over with its humor and humanistic treatment of character and plot. Each of the three characters ultimately commits to the others. The resolve is warm and tender.

As with many short dramas Curfew is the work of an upcoming filmmaker transitioning from another artistic field. Christensen has been a vocalist and guitarist for the band Stellastarr, which formed in Brooklyn in 2000. Not surprisingly Christensen wrote and sang on the Curfew soundtrack. He also edited the film at home on a MacBook Pro computer. Curfew is not unlike the untold number of earlier showcase films, but it points to the potential impact of new, readily available technologies for Oscar-worthy filmmaking at manageable expense. Christensen spent $50,000 on the production, and his Oscar victory was every budding filmmaker’s dream come true. Such things have happened before, of course. Roman Polanski’s acclaimed live-action short Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958) was a graduate-school project produced at the Lodz Film School in Poland. It propelled Polanksi into a career as a renowned international film director.

In addition to their own special niche in film art, classic short films have also inspired feature-length variations. Chris Marker’s time-honored La Jetee (1965) is a kinestatic photo-stills account of the efforts of scientists to project a Third World War survivor back in time with the hopes of staving off the war. Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Monkeys (1995) follows a prisoner sent back in time to find the source of a plague that has killed most of the world’s population. In these netherworld films, past, present, and future intermix freely with “Twilight-Zone” styling.

The 1963 Oscar-winning live-action short An Occurence at Owl Creek Bridge (1961) retold on screen an Ambrose Bierce short story about a Civil War traitor who is set to be hanged. At the moment of his execution the rope appears to break and the traitor drops into the river and swims away. The attending soldiers pursue the fleeing man as he races to return to his family. But in the end, the 30-minute chase turns out to be an extended escape fantasy in the moments preceding the traitor’s death. Robert Enrico’s film inspired the screenplays for Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and Donnie Darko (2001), both about other-world mind fantasies.

All of these examples serve to remind that movie shorts have a role to play in modern cinema. In fact, they can be quite marvelous and they do matter.

Sara S

My husband and I have made a tradition of going to see the animated short films every year at the Michigan Theater since we discovered them 4 years ago. We love them!

Reply

Mary Brunsvold - 61

Too bad Paperman only lasts 58 seconds in video, but I can hear the audio continuing. Why not show the whole short?

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Legal issues preclude us from screening the entire short. Thus, the trailer will have to do. — Editor

Reply

Jay Daves

I have a few dvds at home. Each one is for a certain year. On the dvds for each year are short film nominees along with the winner for that year of the Academy Awards. So, I appreciate short films.

Reply

Gary Linn - 12/73 but class of 74

Wasn’t the story for “An Occurence at Owl Creek Bridge” first adapted for a Twilight Zone episode? Or did TZ just show the short as an episode?

In any case, like to see the shorts and enjoyed the story.

Reply