When time is always short

As a guest lecturer, I am more often asked to talk about my problem-solving techniques than climate science.

Here, after the 2024 Presidential election, that seems appropriate.

Let’s focus on three topics: time, priority, and continuity.

Long time gone

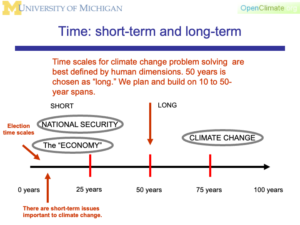

This figure shows a simple time scale in which we consider: What is long term, and what is short term? (Graphic: Ricky Rood.)

Characterizing events and features by a measure of time is common in science and strategic planning. Scientists define this as time scale. It is important in any complex problem to think about time scale. For example, what are the long-term goals? What needs to be done in the short term?

If you are dealing with a crisis, your immediate attention may be focused on emergency demands. And it is common that these short-term demands conflict with the long-term goals.[1]

When I first learned about climate change, I was taught that the time scale for carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was “about 100 years.” That meant if we released a burst of carbon dioxide, it would take about a century for a certain fraction of it to be removed from the atmosphere.

Though this number could be defended from a narrow, atmospheric perspective, it is not an especially useful number for understanding or managing climate change. Even if the carbon comes out of the atmosphere, it does not really go away. Most of it winds up in the ocean and the land. It may, in fact, be released back into the atmosphere. So, that imaginary burst of carbon dioxide entered a cycle and stayed part of a cycle that maintains elevated values of atmospheric carbon dioxide for thousands of years.[2]

There are many different time scales we can use to describe carbon dioxide. Each depends on the specific process we are trying to study or the application we have in mind.

For the purposes of this article, carbon dioxide, once released, exists in the atmosphere for many centuries. This is a long time.

Time scales

When we consider “problem solving,” the time scales that are important to science must be considered in relationship to other parts of the problem. As humans, individually or collectively, we tend to plan in terms of decades. (That is really about our limit.)

In my classes, I often used 50 years to define “a long time scale.” I chose 50 for a few reasons, one being the typical human lifespan. Assuming one starts a career at about 20 years of age, 50 years is a long time to look ahead. Another reason is that if we look at how we plan and build cities and infrastructure, we often use a time horizon of about 30 years, though we generally expect them to last longer than 50.

Here in the U.S., we work on a time scale dictated by our election cycles. Every two years, voters are confronted with some version of climate policy. It is, always, an erratic process with, for example, booms and busts in deploying wind energy turbines being related to tax credits.

The 2008, 2016, 2020, and 2024 Presidential elections, however, have unleashed a series of events of increasing magnitudes.

What’s in your hand?

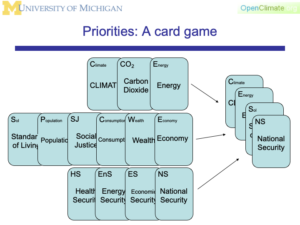

To demonstrate the priority of addressing climate change as a matter of public policy, I developed a little card game. I made a deck of cards, then organized and ranked each one. Imagine the game War in which the highest card wins.

In my deck, I start with three cards: Climate, Carbon Dioxide, and Energy. This would be the set of issues we had to deal with if we considered climate change in isolation. To address climate change, we must reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. To reduce carbon dioxide, we need to intervene and completely alter our management of waste resulting from energy production. The burning of fossil fuels remains the majority source of energy production, despite our real progress in developing renewable energy resources.

Then, I have a bunch of cards like Population, Consumption, Standard of Living, Social Justice, Wealth, and the Economy. These are important ingredients that contribute to Societal Success. The Societal Success cards are very important to us. If our hand contains Societal Failure (like the dreaded Queen of Spades in Hearts), then we are placed on high alarm and can get panicky.

I can add a bunch more cards to the deck: Ozone, Water Resources, Air Pollution, Methane Pollution, and Nitrogen Pollution. They are not necessary to make my point here, because they are comparable in rank with Climate. They could be collected in their own suit, Environment.

Finally, let’s consider the wild cards: Health Security, Energy Security, Economic Security, and National Security.

Our world is full of crises that threaten our security. We always have Health, Energy, Economic, and National Security challenges. Therefore, the Security cards in my deck are always in play and win every hand. The idea of dealing with climate change after we make it through “this crisis” means we never address climate change.

That is why I do not embrace the word “crisis” to describe climate change. There is no evidence that calling it a crisis elevates its rank.

Let’s call it a priority

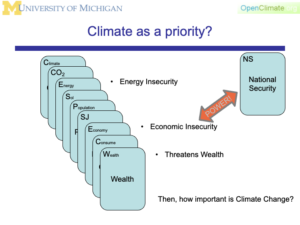

Even in the rare moments without a crisis, energy access and usage are central to our standard of living and economy. Thus, there is always skepticism and resistance to any change regarding energy production.

A fundamental problem is that reducing carbon dioxide emissions does not have an immediate positive effect on climate change. However, we perceive that reducing carbon dioxide emissions does have an immediate negative effect on our standard of living. We are reluctant to sacrifice now (in the 5-10-year period) to improve conditions in the far-off future (50-1,000 years hence).

Even though many people think climate change is important, and as much as we might want that to be true, it is very difficult to elevate its rank in the deck of problems we have to deal with.

The important conclusion in my class is that a climate professional’s job is to keep the Climate card in play — always — while striving to increase its rank in the deck. A skilled player must debunk the myth that playing the Climate card comes at the expense of the Societal Success card, not to mention our ability to address the Security cards.

Continuity: The need for reliable partners

One of the most important elements of complex problem solving is continuity, that is, a consistent, persistent, systematic approach. On the contrary side, one of the easiest and most common ways to ensure a problem will never be solved is by promoting discontinuity: fragmenting, disrupting, and creating doubt and conflict.U.S. elections have always assured discontinuity, and the elections of the last 40 years have gotten increasingly extreme and fragmenting.

Focusing only on climate, our nation’s elections have cast the U.S. as an inconsistent, unreliable player in global policy. We have the largest economy in the world. We are the second-largest current emitter of carbon dioxide, and historically the largest emitter. There is no viable climate policy without participation by the U.S.

As our policy shifts grow larger, doubt increases as to whether we are a reliable partner in many global relationships. Take NATO. If President-elect Trump’s forthcoming administration redefines the NATO alliance and our commitments, we change the whole economic and national security landscape. We set up a situation where the Climate card is always shuffled to the bottom of the deck.

At home, the Project 2025 vision diminishes U.S. governmental institutions, and especially targets climate science. Given the large size and high quality of the U.S. federal science programs, a reduction of scientific capacity would have profound consequences in many fields. This would, in fact, undermine the very culture and practice of scientific research. It would shift the center of scientific research to nations that are more likely to be viewed as adversarial than allied.

Deal me in

Addressing climate change has always been a challenge of balancing short-term versus long-term. Competing priorities make it difficult to keep attention on long-term, persistent problems such as climate change.

I started my classes, in part, because I did not believe we were effective at solving complex problems. We are always challenged by problems where science, especially predictive science, is telling us we need to change some deeply internalized and successful behavior. And at least in the short-term analysis, this election is a tipping point that will require disruptive adaptation to how we do things.

As I shuffle my imaginary deck, I see this moment as a prime opportunity to think about how we play our cards going forward — it’s time to evolve away from our incremental approaches that have proved far too slow.

Thomas Cislo - 1972, 1975

Professor Rood,

Excellent article on a complex and urgent subject. The metaphor of a deck of cards representing the multifaceted nature of the situation underscores the challenge of not-so-easy choices and yet the need for expedient decisions. Thank you.

Reply

Richard Berler

If the market place was a card, and access to non fossils was another card, and prices of non fossils lowered below those of fossil fuels and a similar access to non fossils was achieved as to fossils, would these proposed cards trump the status quo? What might be the time scale of this? These thoughts stemming from the mantra, “it’s the economy, stupid!”

Reply

Jonathan Blanton - 1975

I agree that it is time to evolve away from the current approach to addressing the effects of climate change. The last thing needed is greater movement in the same direction. The most effective and economically beneficial action to mitigate the harmful effects of climate change for our nation and others around the world is continued development of fossil fuel sources and

production using advancing clean technology, modernizing and hardening our energy and power infrastructure, and restarting and expanding nuclear energy power production.

I must disagree with the statement about US Federal science programs and institutions. A huge portion of those programs fund superficial and trivial and poor quality research. The incestuous academic-government bureaucratic complex needs to be reined in and made more lean and accountable, as do most other governmental agencies and institutions.

Reply