Filling a gap: U-M students help combat Michigan’s shortage of rural dentists

Northern Michigan resident Becky Klein was surprised to learn that the dentists at the Thunder Bay Community Health Service clinic were students from the U-M School of Dentistry. They turned out to be just as competent and professional as seasoned practitioners, she said, and excellent communicators.

-

Students create portable device to detect suicide bombers

Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are a major cause of soldier casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan. A group of U-M students won a contest against Ohio State University by developing a new way to detect IEDs—one that is more effective than any currently in use.

-

U-M plans largest ever investment in financial aid

Faced with the toughest economic times since the Great Depression, the University of Michigan Board of Regents voted to approve a general fund budget that calls for $118 million in centrally awarded financial aid, including an 11.7 percent increase in financial aid for undergraduates. The Regents also approved a 5.6 percent tuition increase. The investment in central need-based financial aid is the largest in U-M history.

Related: Applications to U-M continue to reach historic numbers. -

Fossil of primate ancestor discovered

U-M’s Philip Gingerich and Holly Smith are members of an international scientific team that recently announced discovery of a remarkably complete, well-preserved 47-million-year old fossil of an extinct early primate. The fossil is thought to represent an early member of the lineage that gave rise to monkeys, apes and humans.

-

U-M performances celebrate a century of dancing at U-M

Since the first “aesthetic dance” class, taught in 1909, the university has been a locus of dance instruction and a venue for visiting artists from Jose Limon to Martha Graham.

-

The great raid

One night during the Great Depression, police stormed U-M’s fraternities.

-

A life on the edge

Journalist and U-M alumnus Frank Viviano has covered war and conflict around the world. Now living at a slower pace in Italy, his combination of experience and distance give him a uniquely informed perspective on world events—and how to live during these times of crisis.

Columns

-

President's Message

Reaffirming our focus on student access and opportunity

U-M seeks to ensure every student will rise, achieve, and fulfill their dreams. -

Editor's Blog

Peace out

It's a mad, mad, mad, mad world out there. -

Climate Blue

Keeping our focus on climate

As federal support for climate science wanes, Ricky Rood remains hopeful. -

Health Yourself

Are you an ‘ager’ or a ‘youther’?

Why do some people appear younger or older than people born in the same year?

Listen & Subscribe

-

MGo Blue podcasts

Explore the Michigan Athletics series "In the Trenches," "On the Block," and "Conqu'ring Heroes." -

Michigan Ross Podcasts

Check out the series "Business and Society," "Business Beyond Usual," "Working for the Weekend," and "Down to Business." -

Michigan Medicine Podcasts

Hear audio series, news, and stories about the future of health care.

In the news

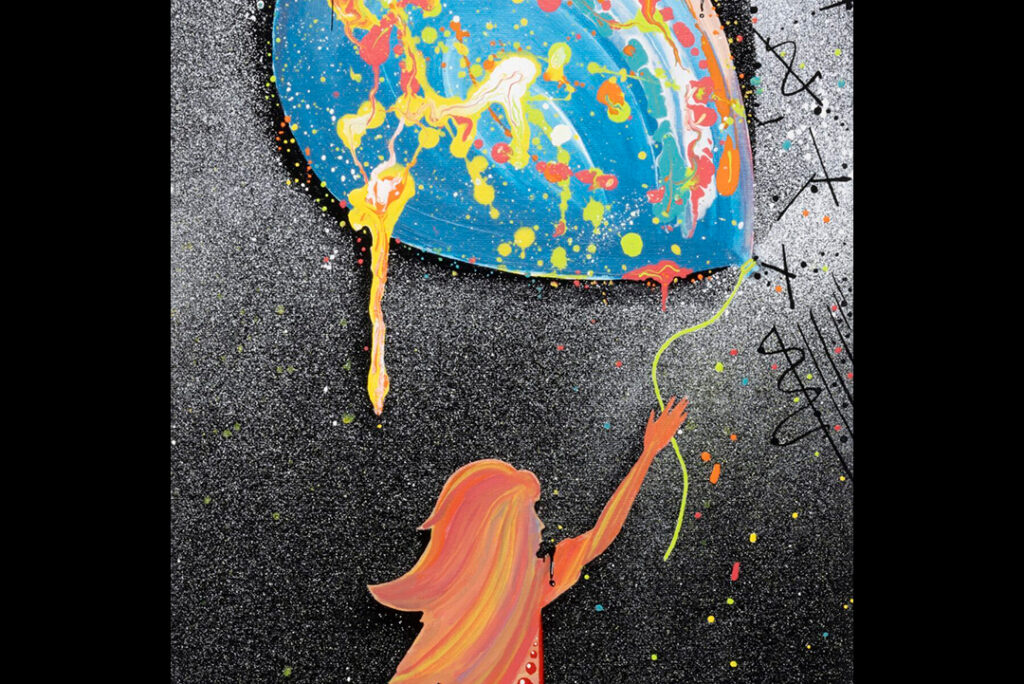

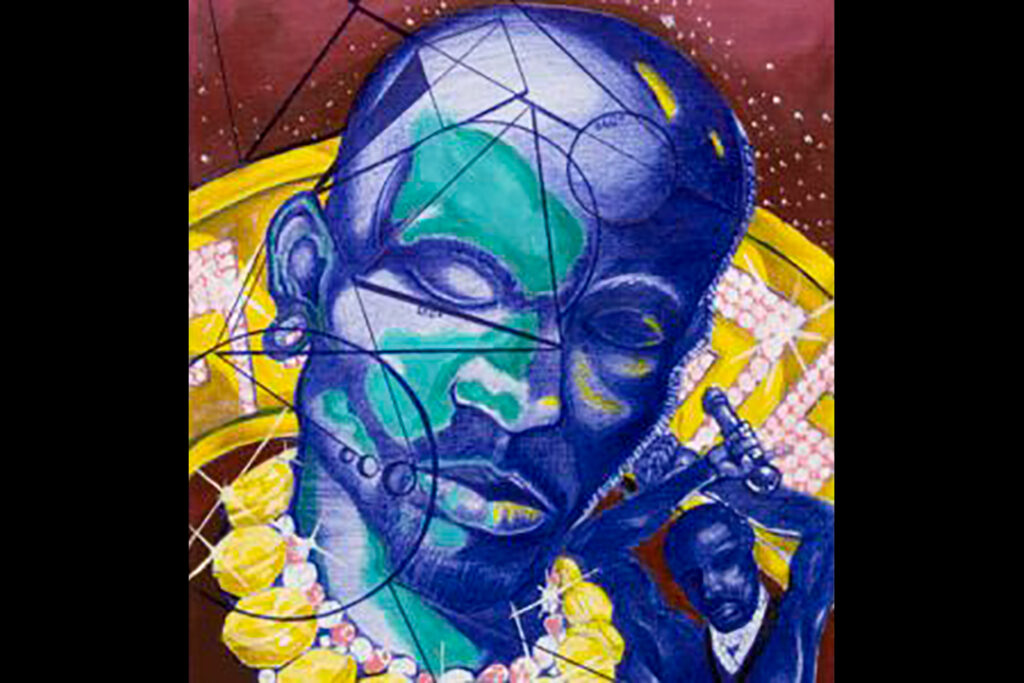

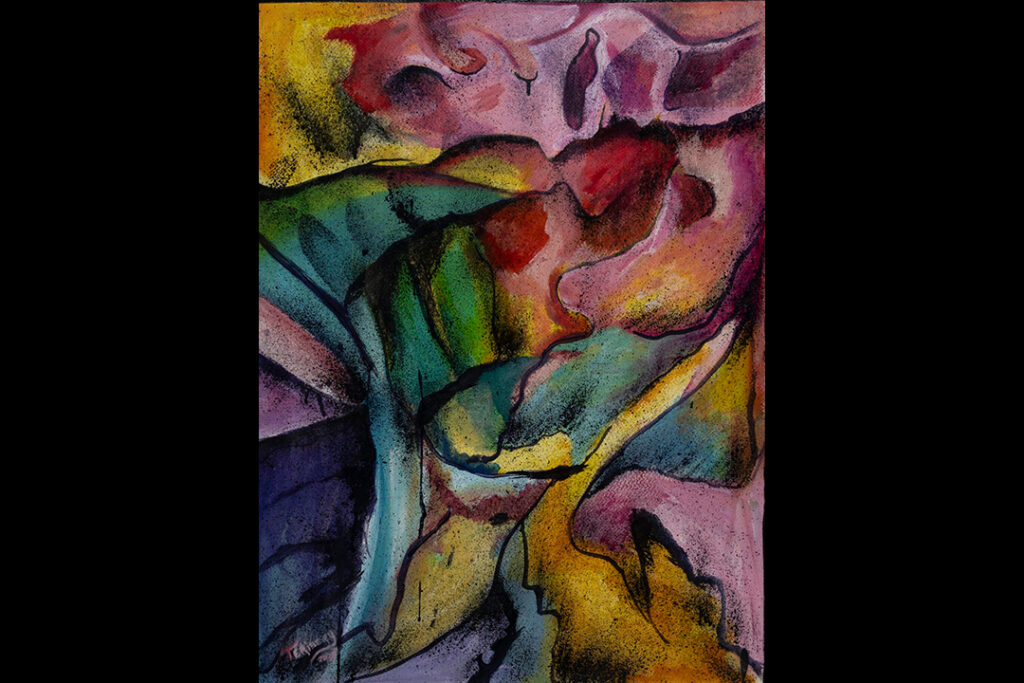

Creativity and connection across prison walls

One of the world’s largest and longest-running exhibitions of incarcerated artists is back with new programming designed to foster connection and deepen public understanding of incarceration in Michigan. The 29th annual Exhibition of Artists in Michigan Prisons, curated by U-M’s Prison Creative Arts Project, showcases 772 artworks by 538 artists incarcerated in 26 state prisons. The Duderstadt Center Gallery on U-M’s North Campus is presenting the artwork through April 1.