Ticket to ride

I have always had a tremendous regard for the road picture in all its varied applications. Foremost, the road picture is an innately cinematic form of storytelling because of the medium’s affinity for the rapid traverse of time and location. This unique aesthetic property has given rise to all sorts of plots with a sustained journey as their structural form. The trio of Dorothy Lamour, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope joked and sang their way through a series of exotic and entertaining road films spanning two decades. The series began in 1940 with Road to Singapore and concluded in 1962 with Road to Hong Kong.

I have always had a tremendous regard for the road picture in all its varied applications. Foremost, the road picture is an innately cinematic form of storytelling because of the medium’s affinity for the rapid traverse of time and location. This unique aesthetic property has given rise to all sorts of plots with a sustained journey as their structural form. The trio of Dorothy Lamour, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope joked and sang their way through a series of exotic and entertaining road films spanning two decades. The series began in 1940 with Road to Singapore and concluded in 1962 with Road to Hong Kong.

The journey film also has been a staple of the western genre: from wagon-train passages to more archetypal tales typified by John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), and more recently Ron Howard’s The Missing (2003). Stagecoach centers on a mythic “ship of fools” idea with disparate dregs of society (a drunkard doctor, a prostitute, a notorious gambler, a whiskey peddler, an ex-convict) loaded onto a stagecoach and driven out of town. Their travel through hostile Monument Valley territory leads to a renewed sense of social purpose and engagement. The Missing, adapted from Thomas Eidson’s novel The Long Ride, involves a classic search-and-destroy mission in which the hero must pursue bad men in uncharted hinterlands, far beyond the frontier’s edge.

Road Warriors

Particularly appealing for me are road pictures that exploit the genre’s (and I do think of it as a genre) potential for social, cultural, and political surveillance within the passing milieu. The 1960s and ’70s were seminal decades for such exploration. The U.S. protest movement against the Vietnam War and the ensuing counterculture era led audiences to embrace the anti-heroic screen gangsters in Arthur Penn’s stylish, socially trenchant Bonnie and Clyde in 1967.

Two years later Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider displayed a range of social and political commentary unlike any American road picture to date. A pair of alienated bikers, Billy and Wyatt (named for two mythic heroes), head for New Orleans hoping to discover the true essence of a country they feel is failing them. As in many road films, the protagonists are a couple with clashing character sensibilities. In Easy Rider, one is a caring sort of individual while the other is wary and cynical of the people they encounter. The duo’s contact with the American landscape offers a bleak revelation. On the road they find drugs, flower children, homophobic police officers, an alcoholic lawyer, prostitutes, and gun-toting, hippie-hating rednecks whose animosity toward Billy and Wyatt brings the film to a fiery climax.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCEeg6-ax6Y?rel=0

The low-budget film was embraced by both audiences and critics. Rex Reed described it as “an excruciating look at where the country is today; about as strong an indictment of America as I’ve seen in any medium.” Charles Champlin of The Los Angeles Times opined: “Easy Rider is an astonishing work of art and an overpowering motion-picture experience. It is also a social document, which is poignant, potent, disturbing, and important.”

Country roads

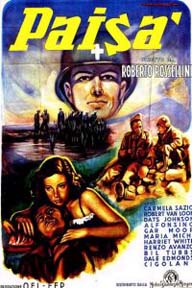

As a professor of film at the University of Michigan I taught courses in national cinema, my favorite a history course on Italian film. Many of the films we studied were road pictures. Like the United States, Italy is a country with distinctly opposing geographic and socio-cultural divisions: North and South, urban and agrarian, European and Mediterranean heritages. These divides lend themselves to the road picture format. Roberto Rossellini’s early films Paisan (1946) and Voyage to Italy (1954) were, respectively, journeys through Italy with nationalistic and personal intent.

As a professor of film at the University of Michigan I taught courses in national cinema, my favorite a history course on Italian film. Many of the films we studied were road pictures. Like the United States, Italy is a country with distinctly opposing geographic and socio-cultural divisions: North and South, urban and agrarian, European and Mediterranean heritages. These divides lend themselves to the road picture format. Roberto Rossellini’s early films Paisan (1946) and Voyage to Italy (1954) were, respectively, journeys through Italy with nationalistic and personal intent.

Paisan, in six narrative vignettes, moved up from Sicily to Naples and on to Rome and Florence with a conclusion set in the Po Valley. It sought to create a sense of national identity by depicting the various people of Italy during World War II. Voyage to Italy focused on an English couple (Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) who, experiencing difficulties in their marriage, appear to resolve their differences as they discover the country’s treasures. Federico Fellini’s great road picture La Strada (1954) offered a Pirandellian narrative about human relations and self-knowledge. The picaresque plot involves a traveling road performer (Anthony Quinn) and a slow-witted, but lovable assistant (Giulietta Masina). The journey leads one character to love and affection while the other remains apathetic until it’s too late to act on suppressed feelings.

Road work ahead

As luck would have it, my annual research trip to the British Film Institute last month got me to London in time for a screening retrospective of the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, that most inventive and challenging of 20th-century Italian directors. The retrospective included The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), one of Italy’s most intriguing films.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUxizZJ-UAk?rel=0

Pasolini was born in Bologna in 1922 and studied at its university where he earned a doctorate in Italian medieval and Renaissance art history. He ventured into film as an assistant writer on Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria in 1957, and then began writing and directing his own films in the early ’60s. Three early efforts drew on the traditions of Italian neo-realism before Pasolini made an abrupt departure toward avant-garde symbolic filmmaking with The Hawks and the Sparrows in 1966. I had never seen this Pasolini work and I was enthralled by it. The film is a symbol-laden experience with allegorical allusions to the many social, political, and religious issues pressing on Pasolini’s intellectual and aesthetic thinking at the time of its creation.

As a road picture, the evolving journey is fragmentary and spontaneous in its development. The principal characters are a father and son, Toto and Ninetto (Nino). At the film’s outset we see the two ambling merrily down a country road. On their journey they encounter an assortment of characters (all played by non-actors) whose situations touch allegorically on issues of economic uncertainty, poverty, and hunger. One woman boils birds’ nests for their possible nutrients. Living environments and the passing milieu are starkly desolate. Pasolini’s road vision is that of a country in the midst of social and political evolution with no clear sense of forward momentum. To deal in a concrete way with this vision, Pasolini intercuts documentary newsreel footage of the 1964 funeral of communist leader Palmiro Togliatti with fictionalized footage of Nino and Toto appearing to observe the funeral procession. “What does this historic moment mean for Italy?” the film seems to be asking.

As heavily laden as it is with ideological allusions, The Hawks and the Sparrows is rich in sardonic wit. Toto, the most beloved of all Italian film clowns, spearheads the humor. Costumed to look like a blend of a stoic Buster Keaton and an animated Charlie Chaplin, Toto is both a charming and dispassionate traveler, seemingly untouched by the world around him. He does enjoy a romp in the fields with a roadside prostitute as does his cheerful, empty-headed sidekick of a son. A satirical take on Marxism comes in the presence of a talking crow that joins Toto and Nino on their journey. Coming from the Country of Ideology and living on Karl Marx Street, the crow squawks out (with Pasolini doing the voice) so many tired ideological truisms that the disgusted father and son ultimately kill the bird and eat it. Christianity also is satirized when Nino and Toto are commissioned as St. Francis-like monks who set about evangelizing the “arrogant hawks” and “humble sparrows” who’ve long been adversaries. The duo fails at resolving the eternal conflict, but Toto’s communication efforts with the birds are hilarious.

As heavily laden as it is with ideological allusions, The Hawks and the Sparrows is rich in sardonic wit. Toto, the most beloved of all Italian film clowns, spearheads the humor. Costumed to look like a blend of a stoic Buster Keaton and an animated Charlie Chaplin, Toto is both a charming and dispassionate traveler, seemingly untouched by the world around him. He does enjoy a romp in the fields with a roadside prostitute as does his cheerful, empty-headed sidekick of a son. A satirical take on Marxism comes in the presence of a talking crow that joins Toto and Nino on their journey. Coming from the Country of Ideology and living on Karl Marx Street, the crow squawks out (with Pasolini doing the voice) so many tired ideological truisms that the disgusted father and son ultimately kill the bird and eat it. Christianity also is satirized when Nino and Toto are commissioned as St. Francis-like monks who set about evangelizing the “arrogant hawks” and “humble sparrows” who’ve long been adversaries. The duo fails at resolving the eternal conflict, but Toto’s communication efforts with the birds are hilarious.

As a road picture The Hawks and the Sparrows is one of the most challenging. Yet even with its often confusing allusions and ideological playfulness, it’s a film one is not likely to forget. It’s also a final unveiling of Toto’s great comic talents, captured on film the year before his death at age 69. Pasolini would go on to make other mythic and often shocking films, e.g., The Canterbury Tales (1972), The Arabian Nights (1974), and Salo: Or the 120 Days of Sodom (1974). But in interviews before his tragic death in 1975, he often spoke of The Hawks and the Sparrows as his greatest, most personally satisfying cinematic achievement. As I watched the film and reflected on it, I couldn’t help but wonder what kind of film Pasolini, if alive today, might make about the current socio-political uncertainties in 2013 Italy. The possibilities would be great.

Road trippin’

On a lighter note: Listed below are a dozen of my favorite road pictures. I recommend them all.

- It Happened One Night (1934)—romantic comedy

- The Grapes Of Wrath (1940)—social realism

- Two for the Road (1967)—a couple’s journey in France recalls their past

- Deliverance (1972)—a group trip into a Southern heart of darkness

- Harry and Tonto (1974)—a New York widower and his cat head for California

- Thieves Like Us (1974)—Altman’s lovely take on two small-time gangsters

- The Passenger (1975)—Antonioni’s mystery journey with Jack Nicholson

- Apocalypse Now (1979)—Coppola’s Vietnam heart of darkness

- Thelma And Louise (1991)—two females on a vacation journey that turns dark

- My Own Private Idaho (1991)—two young male drifters on the road

- The Stolen Children (1992)—an Italian carabinier on the road with two orphans

- Little Miss Sunshine (2006)—the family comedy/road picture at its best

What have I missed that you would have included?

Geoff Baker - 82 LSA

Hello Frank from Geoff,

Fond memories of studying many of these great films through your class. Hoping you and all of the Beavers are very well.

God Bless – Geoff Baker

Reply

Victoria Green

Thank you so much for the list, Professor Beaver! Many of my non-traditional college students (aged 17-70+) would love to have a film course like those I took with you in the mid-1980s, but their various curricula never include “frills.” They really enjoy getting movie lists like these. Among other things, watching a recommended movie gives them an educationally sanctioned excuse to take a break! Interestingly, it seems the older a student is, the more likely they believe familiarity with “good movies” will help them find common ground with potential employers. I can’t say that I disagree.

Many thanks!

— Vicki Green, 1988

Reply

Aimee Hachigian-Gould - 1976 B.S., 1979 M.D.

Elia Kazan’s powerful, dark and finally uplifting movie, America, America, should make the list.

Reply

Ted Hall - BS 1979, M.Arch 1981, Arch.D. 1994

The Ultimate Road Trip — or rather, a trans-generational series of road trips: “2001: A Space Odyssey”

Reply

Karen Bayekian-Kalinowski - BA'77 MA'78

Professor Beaver I too have fond memories of your classes. I’d add Rain Man to the list.

Reply

Harvey Hamburgh

I loved STOLEN CHILDREN. Can someone find me a dvd with English subtitles, as when I saw it in the theatre? I can only find the original Italian (not dvd compatible). Grazie!

Reply