Raising the steaks

The idyllic picture of the family farm where agriculture and animal production integrates to benefit the farmer and society is a long-lost fantasy. Don’t be fooled by advertisers that try to paint a picture of 21st-century food production applied to the family farm. Instead, what we have is a system of intensive food production featuring enormous single-crop farms and animal production facilities.

Initially, industrial agriculture and meat production were hailed as technological triumphs that would enable a skyrocketing world population to feed itself. Instead, a growing number of farmers, environmentalists, scientists, and policymakers see present-day food production methods as a mistaken application of a systems approach better suited for making computers and washing machines, not food.

Industrial food production: The monoculture

At the center of industrial food production is monoculture — the practice of growing single crops intensively on a very large scale. Corn, wheat, soybeans, cotton, and rice are all commonly grown this way, mostly in the United States. Monoculture relies heavily on chemical inputs such as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. The fertilizers are needed because growing the same plant (and nothing else) in the same place year after year quickly depletes the nutrients the plant relies on (and these nutrients have to be replenished somehow). The pesticides are needed because monoculture fields are highly attractive to certain weeds and insect pests.

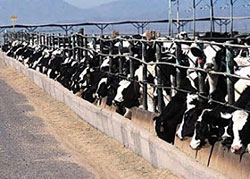

Similarly, in industrial meat production, most beef cattle spend the first months of their lives (and perhaps up to a year) on pasture or rangeland, where they graze on forage crops such as grass and alfalfa. Thereafter most U.S. beef cattle are “finished” — prepared for slaughter — at large-scale facilities called animal feeding operations (AFOs), also referred to as CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations), where they are fed grain, mostly corn. Essentially, a CAFO confines animals for more than 45 days in a vegetation-free area where vegetation, forage growth, or post-harvest residues are not sustained in the normal growing season over any portion of the lot or facility.

Similarly, in industrial meat production, most beef cattle spend the first months of their lives (and perhaps up to a year) on pasture or rangeland, where they graze on forage crops such as grass and alfalfa. Thereafter most U.S. beef cattle are “finished” — prepared for slaughter — at large-scale facilities called animal feeding operations (AFOs), also referred to as CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations), where they are fed grain, mostly corn. Essentially, a CAFO confines animals for more than 45 days in a vegetation-free area where vegetation, forage growth, or post-harvest residues are not sustained in the normal growing season over any portion of the lot or facility.

CAFOs include open feedlots, as well as massive, windowless buildings where livestock are confined in boxes or stalls. Other terms used to describe a CAFO include mega farm, animal factory, and industrial farm.

Here’s how the Environmental Protection Agency describes these operations on their website:

“AFOs generally congregate animals, feed, manure, dead animals, and production operations on a small land area. Feed is brought to the animals rather than the animals grazing or otherwise seeking feed in pastures. Animal waste and wastewater can enter water bodies from spills or breaks of waste storage structures (due to accidents or excessive rain), and nonagricultural application of manure to crop land.”

In CAFOs, an animal’s mobility is necessarily restricted due to limited space. The animals are fed a high-calorie, grain-based diet, often supplemented with antibiotics and hormones, to maximize weight gain. Their waste concentrates and often becomes an environmental problem, not the convenient source of fertilizer (manure).

Confined dining

The exact number of CAFOs in the U.S. is not easy to pin down. In its 2008 report, CAFOs Uncovered, the Union of Concerned Scientists wrote, “Although they comprise only about five percent of all U.S. animal operations, CAFOs now produce more than 50 percent of our food animals.”

The exact number of CAFOs in the U.S. is not easy to pin down. In its 2008 report, CAFOs Uncovered, the Union of Concerned Scientists wrote, “Although they comprise only about five percent of all U.S. animal operations, CAFOs now produce more than 50 percent of our food animals.”

That was six years ago, and there is evidence that the number of CAFOs — especially in the Midwest — has increased.

Quoting from Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2009 well- researched book Eating Animals: “Roughly 450 billion land animals are now factory farmed every year. Ninety-nine percent of all land animals eaten or used to produce milk and eggs in the United States are factory farmed.”

For beef alone, current estimates suggest CAFOs account for a minimum of 50-65 percent of the beef consumed in the United States. And the trend is not abating.

Consider this: In 1966, it took one million farms to house 57 million pigs; by the year 2001, it only took 80,000 farms to house the same number of pigs, and in 2013 there are slightly more than 66 million pigs in less than 69,000 farms. In other words, we’ve taken slightly more pigs and crammed them into a smaller space.

The many problems of CAFO-produced food or Can you say “toxic poo?”

First, putting large numbers of animals together in a relatively small area produces a huge amount of manure. Storage and disposal of this manure presents environmental and health challenges, to say the least.

Also, more than 168 gases are emitted from CAFO waste, including hazardous chemicals such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and methane.

According to reliable sources, CAFOs produce about 65 percent of our country’s manure, or about 300 million tons per year — that’s double the amount of poo generated by all the people in the U.S.

Some of the manure created in these facilities gets spread on farm fields, which do absorb a portion of the nitrogen (while the rest erodes into waterways, leaches into the groundwater, and — ultimately — adds nitrous oxide (N2O), a dangerous greenhouse gas, to the atmosphere).

Unfortunately, a great deal of the excess manure ends up in holding areas, or “lagoons” producing toxic fumes and high-nutrient (not in a good way) waste that often leak into streams and well water. The EPA reports that CAFO waste has polluted more than 35,000 miles of river and groundwater in 17 states. A prime example of CAFO-induced pollution can be found in the Baron Fork Creek, Flint Creek, and Illinois River, all of which flow through Oklahoma. Much of this area is noted for its aesthetic, ecological, recreational, and water quality.

Unfortunately, a great deal of the excess manure ends up in holding areas, or “lagoons” producing toxic fumes and high-nutrient (not in a good way) waste that often leak into streams and well water. The EPA reports that CAFO waste has polluted more than 35,000 miles of river and groundwater in 17 states. A prime example of CAFO-induced pollution can be found in the Baron Fork Creek, Flint Creek, and Illinois River, all of which flow through Oklahoma. Much of this area is noted for its aesthetic, ecological, recreational, and water quality.

However, as a result of industrial-scale feeding operations in the area, the water quality was seriously impaired to the point where the state sued the CAFO companies to stop polluting their waterways. This is happening more and more in many states.

The issue of antibiotics

The extreme crowding in CAFOs puts animals under tremendous stress. Some animals become aggressive (you might be too, if you were locked in a small area with no chance to recreate). Many become ill. CAFOs use routine, sub-therapeutic doses of growth promoters or prophylactic antibiotics to both prevent disease and make animals grow faster. In fact, a frightening 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. go for animal use in CAFOs.

Overuse also has led to antibiotic-resistant bacteria in meat, and — perhaps even scarier — some of these bacteria can and have found their way into meat sold at the store and right into our food supply. While there is no direct evidence that high levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from CAFO operations are yet a threat to the nation’s health, the CDC and the World Health Organization have called for an end to the nontherapeutic use of these drugs for animals. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration announced in July 2009 that the Obama administration supports ending nontherapeutic use of antibiotics in livestock. And in December 2013 the Food and Drug Administration announced new policies to curtail the widespread use of antibiotics in cows, pigs, and chickens raised for food. Critics say the moves didn’t go nearly far enough.

Increased burden on taxpayers

One of the arguments in favor of industrial animal production is cost savings and the ability to bring to the marketplace (high-quality) inexpensive meat. While CAFOs appear to operate efficiently, this is clouded by the fact they are indirectly supported by taxpayers in the form of taxpayer-funded subsidies to grain farmers. These subsidies (i.e., the federal farm bill) result in artificially low grain prices for corn, soybeans, and other grain operations that eventually sell to CAFOs. Cheap feed enables CAFOs to lower costs of production while maintaining their same levels of profit – this in effect stifles competition with pasture-based agriculture that does not receive the same level of taxpayer support.

Decreased meat quality

Comparisons of meat from pasture-feed operations compared to meat from CAFOs indicates the meat from pasture-raised cattle, for example, contains less total fat — and higher levels of certain fats that appear to provide health benefits. These nutrition differences arise from chemical differences between forage and grains, and the complex ways in which ruminant animals (cattle) process these feeds.

Most of the published studies that compare levels of different kinds of fat from pasture-raised milk and meat with levels found in CAFO-produced milk and meat show clear statistical differences.

There appears sufficient scientific evidence for the following claims regarding the health benefits of grass-fed beef compared to CAFO-produced meat:

- Steak and ground beef from grass-fed cattle can be labeled “lean” or “extra lean.” This is seldom true for conventionally (CAFO) raised cattle.

- Some steak from grass-fed cattle can be labeled “lower in total fat” than steak from conventionally raised cattle.

- Steak from grass-fed cattle can carry the health claim that “foods low in total fat may reduce the risk of cancer.”

- Steak and ground beef from grass-fed cattle can carry the “qualified” health claim that foods containing the omega-3 fatty acids EPA (Eicosapentaenoic acid — an omega-3 fatty acid known to lower inflammatory processes) or DHA (Docosahexaenoic acid — also an omega-3 fatty acid and a primary structural component of the human brain, cerebral cortex, skin, and sperm) may reduce the risk of heart disease.

As more is learned about health effects of grass-fed cattle compared to conventionally raised cattle, new standards may be issued that would allow food purveyors to make further health claims.

How can you know if the meat you buy is from a CAFO?

The answer is easy — you can’t.

That’s because meat from animals raised in CAFOs looks the same as any other — and it isn’t labeled. In fact, the onus remains on the relatively small percent of pasture-fed meat producers who are trying to do something else — whether it’s use of organic feed, raising animals in smaller numbers, or keeping them on pasture — to make their practices known through labels that are often hidden or perceived as something extra.

Look for labels that say “grass-fed,” “grass-finished,” and “pasture-raised.” If it specifically does not say it you can pretty much assume that “normal meat” = CAFO meat.

Better yet, to avoid CAFO meat:

- Find a farm in your area that raises animals on a pasture (a farmers market is a great place to start the hunt).

- Try to buy fresh meat, not packaged meat — most packaged meat comes from CAFOs unless specifically labeled.

- Be willing to spend a little more for grass-fed, pasture-raised meat.

- Before ordering meat at a restaurant, ask if they know where it came from. If they don’t, it’s a safe bet it came from a CAFO.

References:

Economic Research Service (ERS). 2008. Foodborne illness cost calculator. U.S. Department of Agriculture. www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodborneIllness.

Foer, J.S. 2009. Eating Animals. Little, Brown and Company. Hachette Book Group. New York. ISBN: 978-0-316-08664-6.

Greener, C.K. 2006. Pastures: How grass-fed beef and milk contribute to health eating. Union of Concerned Scientists. UCS Publications, Two Brattle Square, Cambridge, MA 02238-9105.

Gurian-Sherman, D. 2008. CAFOs Uncovered: The Untold Costs of Confined Animal Feeding Operations. Union of Concerned Scientists. UCS Publications, Two Brattle Square, Cambridge, MA 02238-9105.

Examination of the Potential Human Health, Water Quality and other Impacts of the Confined Animal Feeding Operation Industry. Hearing Before the Committee on Environment and Public Works United States Senate- One Hundred Tenth Congress. First Session, Sept. 6, 2007. Printed for the use of the Committee on Environment and Public Works.

John MacKenzie - 1950

Wonderful, informative article.

Reply

Gary Schneider

WOW!! You’ve taken on the meat industry!!

Well done! And beautifully-written.

Thanks.

Reply

Kari Magill - 1984

The one action missing in the list of ways to avoid eating CAFO meat: Don’t eat meat! If all of us even cut down on our meat consumption (for example, utilizing the British concept of “Meat Free Mondays,” such production techniques would not be necessary.

Reply

Fred Ingersoll

Wow, I’m amazed that a so called “researcher” can get away with publishing such drivel and only being able to back it up with two references from the Union of Concerned Scientists and a book called “Eating Animals”. Those both sound like two “unbiased” resources to use to draw conclusions. I know UM hates to acknowledge that “other school” up the road in East Lansing, but maybe if you had spent a little time talking to their world renowned animal science department or their agricultural economists, at least you could have had a semblance of scientific integrity in your article. Or at a minimum, you could have talked to some farm groups, ranch groups or someone from the meat industry to get a different viewpoint, but then that would have probably interfered with your agenda.

Since it is pretty obvious you have never stepped foot on a farm or have a clue about farming, good luck finding local cattle that are “grazing on pasture”, as I look at the two feet of snow on the ground.

Reply

Steven Hewlett - 1975

Fred, you do know about hay, don’t you? Or maybe silage? You cut it in the spring and feed it in the winter. It is possible to get grass feed meat in the winter. I just bought some at Arbor Farms in Ann Arbor today.

Reply

Fred Ingersoll

Sure, I know about hay, haylage, corn stover, oatlage, corn silage and a few dozen other feed stuffs. But that is not the same as “pasture raised”. In fact, many of those products are used in confinement settings, i.e. feedlots. So is the point of the article “what they eat” or “where they eat”? I doubt if the author knows the difference.

Reply