Good medicine?

When the cannabis flower is ground-up and smoked using different methods, its ingredients (primarily THC) quickly diffuse to the brain and elicit a perceived high within seconds to minutes.

In my September 2018 column, “Cannabis and health: Part 1,” I described cannabis’ ingredients, outlined history of its use, and raised two questions regarding its potential medical benefits:

(1) Can cannabis relieve health problems?

(2) Are there negative effects of cannabis use?

In this issue of Health Yourself, I attempt to answer these questions using evidence-based science.

U.S. medical-marijuana users

In 1996, California voters passed Proposition 215, making it the first state in the union to legalize medical use of marijuana Thirty more states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico have enacted similar laws.

Colorado has the largest number of medical marijuana users in the U.S., with 19.8 patients per 1,000 state residents. Arizona, Nevada, and California tie for the second largest number, with 19.4 patients per thousand residents, and Washington and Oregon each come in third with 19.2 patients per 1,000 state residents.

Using the ratio of total patients to every 1,000 state residents and extrapolating to all 50 states, it is possible to estimate the total number of medical marijuana users in the country at approximately 2.6 million. This corresponds to a national average of 8.1 medical marijuana users per thousand people or 0.81 percent of Americans. For context, the number of Americans who ate a plant-based diet in 2015 comprised only 0.5 percent of the U.S. population (see my previous Health Yourself on whole-food, plant-based nutrition.) With the fact that plant-based food revenues continue to grow at 8 percent per year, the vast potential for profit in the medical-cannabis industry becomes clear.

Some 92 percent of medical-marijuana users report it works for them, and according to a study published in 2013, eight of 10 doctors approve selective use of medical marijuana. The most common conditions for medical marijuana use (in Colorado and Oregon) are severe pain (89.4 percent of patients), spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis (20.5 percent of patients), nausea (10.5 percent of patients), post-traumatic stress disorder (10 percent of patients), cancer (6.3 percent of patients), epilepsy (3.9 percent of patients), cachexia (2.7 percent of patients), glaucoma (1.5 percent of patients), and HIV/AIDS (0.9 percent of patients).

Factors that affect cannabis effectiveness

Vaping represents the process of inhaling the vapor produced by an e-cigarette or personal vaporizer that heats a liquid/chemical product (nicotine, THC-cannabis, etc.).

Potency. In the 1990s and early 2000s, most cannabis consumed in the U.S. was grown abroad and illicitly imported. Much of this was low potency. During the last decade or so, high-potency cannabis produced within the U.S. is increasingly common. In 1995, the average potency of marijuana was 4 percent. It’s roughly 12-30 percent now. The potency impacts the effects of relaxation, euphoria, and other systemic effects.

Since the late 1960s, the federal government has mandated that all marijuana used in research comes through the federal government – grown at a single facility at the University of Mississippi. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) oversees the operation. Complaints from researchers indicate that federal marijuana is inferior with respect to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) potency. The highest THC cigarette the government produces tops out at 6.7 percent. Not a single government strain tests over 10.2 percent THC. Compare that to the average 25 percent THC for marijuana cigarettes sold in California and other states. Also, the federal government has no high-cannabidiol products, whereas high-CBD products are common in many cannabis markets. Because of this, federally sponsored cannabis research becomes suspect.

Route of administration. The route of administration of cannabis affects the onset, intensity, and duration of its effects (particularly psychotropic), the effects on organ systems, and the addictive potential and negative consequences associated with its use. There are four common routes of cannabis administration.

-

- Smoking. When the cannabis flower is ground up and smoked using different methods, its ingredients (primarily THC) quickly diffuse to the brain and elicit a perceived high within seconds to minutes. Blood levels of THC reach a maximum after about 30 minutes and then subside rapidly within 1-3.5 hrs.

- Vaping. Vaping represents the process of inhaling the vapor produced by an e-cigarette or personal vaporizer that heats a liquid/chemical product (nicotine, THC-cannabis, etc.).

-

Dabs are concentrated doses of cannabis made by extracting THC and other cannabinoids using a solvent (butane or carbon dioxide), resulting in sticky oils, commonly referred to as wax, shatter, budder, or butane hash oil (BHO). They’re heated on a hot surface and then inhaled.

Dabbing. Dabs are concentrated doses of cannabis made by extracting THC and other cannabinoids using a solvent (butane or carbon dioxide), resulting in sticky oils. These are commonly referred to as wax, shatter, budder, or butane hash oil. They’re heated on a hot surface and then inhaled.

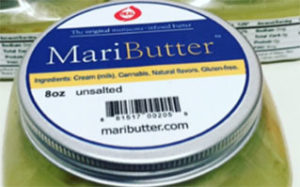

- Eating. Different parts of the cannabis plant are mixed, cooked, and dissolved into other foods. For example, marijuana butter (aka MariButter) is butter melted and mixed with THC. Edibles generally do not produce effects for 30 minutes to 2 hours and can last 5-8 hours, or longer.

Therapeutic effects of cannabis and cannabinoids

Cannabis sativa has a long history as a medicinal plant, dating back more than two millennia. It was available as a licensed medicine listed in the U.S. pharmacopoeia from 1851-1941.

In 1999, the Health and Medicine Division (formally the Institute of Medicine-IOM) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a report on the potential therapeutic uses for cannabis. It is one of the first and most widely referenced consensus statements, based on the best scientific evidence at the time. Among the general conclusions:

- The natural role of cannabinoids in immune function is likely multi-faceted and remains unclear.

- The brain develops tolerance to cannabinoids.

- Animal research demonstrates the potential for dependence, but the potential is less than with benzodiazepines, opiates, cocaine, or nicotine.

- Withdrawal symptoms can be observed in animals but appear to be mild compared to opiates or benzodiazepines, such as diazepam (Valium).

- Scientific data indicate the potential therapeutic value of cannabinoid drugs — primarily THC — for pain relief, control of nausea and vomiting, and appetite stimulation. Smoked marijuana, however, is a crude THC delivery system that brings harmful substances with it.

- The psychological effects of cannabinoids, such as anxiety reduction, sedation, and euphoria are potentially undesirable for certain patients and situations and beneficial for others.

- Numerous studies suggest that marijuana smoke is an important risk factor in the development of respiratory disease.

- A distinctive marijuana withdrawal syndrome has been identified, but it is mild and short-lived. The syndrome includes restlessness, irritability, mild agitation, insomnia, sleep disturbance, nausea, and cramping.

Since 1999, researchers have undertaken a plethora of cannabis-centric research, some supporting and some refuting the HMD 1999 conclusions. In 2017, the HMD released an updated review of research on medical marijuana. This report represents the most current scientific consensus regarding its use.

Based on the evidence

Like most clinical science outcomes, conclusions and consensus rest on the quality of the research and what is known as “the preponderance of evidence.”

- Conclusive and/or substantial evidence is the ideal outcome, and usually translates to clinical use.

- Moderate evidence is still strong but requires further confirming studies and has limited use in clinical practice.

- Limited evidence suggests a possible trend, but certainly does not represent consensus or clinical finding.

Before a drug finds its way into clinical practice it is backed by conclusive and/or substantial evidence that includes acute and long-term clinical trials involving random-controlled trials. Such research requires significant time and resources. And since it is difficult to monetize cannabis (anyone can grow and cultivate it), cannabis research as a pharmaceutical is still in its infancy.

Below, I present the latest consensus findings on cannabis’ use as an accepted pharmaceutical. I present only findings and conclusions based on substantial and moderate evidence, as this research is most likely to translate to future clinical use. I also have chosen to present conclusions where there currently is insufficient evidence to support specific claims of cannabis’ health effects.

Cannabis’ effects on cancer |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support these claims |

|

Cannabis’ effects on cardiometabolic risk (heart attack, metabolic dysregulation, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and diabetes) |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support this claim |

|

Cannabis’ effects on pulmonary function and respiratory disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, asthma) |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support these claims |

|

Cannabis’ effects on immunity |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support these claims |

|

Cannabis’ effects on injury and death |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support these claims |

|

Cannabis’ effects on pregnancy and childbirth |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support this claim |

|

Cannabis’ effects on psychosocial behavior, including cognition, academic achievement, employment and income, and social relationships |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support this claim |

|

Cannabis’ effects on mental health |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence to support these claims |

|

Potential adverse effects

Different parts of the cannabis plant are mixed, cooked and dissolved into other foods. For example, marijuana butter (aka MariButter) is butter melted and mixed with THC. Edibles generally do not produce effects for 30 minutes to 2 hours and can last 5- 8 hours, or longer.

Because of differences in cannabis potency, mode of administration, obtaining truthful self-reported data, and lack of trusted double-blind research methodology, studying potential adverse effects of medical marijuana becomes complicated. Most research on adverse effects uses cross-sectional design research and relies on self-reported health.

A recent longitudinal study followed more than a thousand individuals from birth to age 38, testing associations between decades of cannabis use and 12 health outcome measures. The findings were revealing. Tobacco use associated with the worse health outcome for 8 of the 12 health variables while cannabis use associated with just one: gum disease. Go figure!

In another longitudinal study, the longest on cannabis and mortality, researchers followed 50,000 men as they approached age 60, about 30 years after first reporting on this cohort’s health status. In the first study of these subjects at about age 30, researchers found no significant excess mortality among habitual cannabis users. In the follow-up study, habitual cannabis users did have a significantly higher risk (40 percent) of dying prematurely, but this was not linked directly to cannabis use. Instead, cannabis was indirectly related to premature death. So, when a person under the influence of cannabis runs across a street without looking and gets hit by a car, the direct cause of death would be listed as hit-and-run. But, certainly cannabis contributed to the person’s death.

Cannabis use disorders (CUD)

Cannabis use, either erratic, intermittent, or habitual, is not without risks and problems. A major contributor to this issue is a lack of consensus regarding what constitutes a cannabis use disorder (CUD). CUD represents a diagnosable psychiatric disorder defined as “a problematic pattern of cannabis use leading to clinically significant personal, social, physical, and/or psychological distress or impairment.”

Because of confusion in terminology and scope of what constitutes “problem” cannabis use, research in this area is less well established. Nevertheless, a summary of the research evidence reveals some interesting and provocative conclusions.

Cannabis Use Disorders |

|

| Conclusive/substantial evidence |

|

| Moderate evidence |

|

| No/insufficient evidence |

|

Cannabis intoxication

During acute cannabis intoxication, sociability, and sensitivity to certain stimuli (e.g., colors, music) are often enhanced, perception of time altered, and appetite for sweet and fatty foods heightened. Many users report feeling relaxed or experiencing a pleasurable “rush” or “buzz” after smoking cannabis. These subjective effects often associate with decreased short-term memory, dry mouth, and impaired perception and motor skills. When intoxicated, many users report increased panic attacks, paranoid thoughts, hallucinations, or the drive to sleep. Some users report impaired driving abilities, although this has not been well documented.

Finally, cannabis use generally stimulates aggressive food consumption – “the munchies” – resulting in large ingestion of calories. A recent study showed that cannabis consumption influences appetite by triggering the release of a hunger hormone called ghrelin, released by the stomach when it is empty, signaling to the brain that it’s time to eat. A cannabis-induced ghrelin surge results in the rapid consumption of food, on a consistent basis.

Summary

At present, it appears the only substantial evidence supporting medical cannabis use is for treating chronic pain in adults, chemo-induced nausea and vomiting, and relieving self-reported muscle tightness in patients with MS. Other moderate (and limited) evidence exists, but more large-scale clinical trials are needed, using marijuana with different potency levels, to enable health-care professionals to make sound decisions regarding the efficacy of these findings.

Because cannabis is a naturally occurring plant, and cannot be patented, there appears little enthusiasm for the pharmaceutical industry to conduct research, and the U.S. government policy on cannabis discourages research that may reveal cannabis belongs as a viable medical option. We need more research on cannabis and its health effects now!

References

-

- Agrawal, A., et al. “Initial reactions to tobacco and cannabis smoking: A twin study.” Addiction 2014;109(4):663.

- Bergamaschi, M., et al. “Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naive social phobia patients.” Neuropsychopharmacology 2011;36(6):1219.

- Borchardt, D. “Marijuana Sales Totaled $6.7 Billion in 2016.” forbes.com, Jan. 3, 2017.

- Bovasso, G.B. “Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms.” American Journal of Psychiatry 20011;58(12):2033.

- Cascini, F., et al. “Increasing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ-9-THC) content in herbal cannabis over time: Systematic review and meta-analysis.” Current Drug Abuse Reviews 2012;5(1):32.

- Chen, C.Y., et al. “Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2005;79(1):11.

- Center for Medical Cannabis Research. 2016. “Research: Active studies, pending studies, completed studies, discontinued studies.”

- Davis, J. “Brain changes responsible for the appetite effects of cannabis identified in animal studies.” 2018. Paper presented at 26th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior.

- Degenhardt, L., Hall, W. “Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease.” Lancet 2012;379(9810):55.

- Greydanus, D.E., et al. “Cannabis: The never-ending, nefarious nepenthe of the 21st century. What should the clinician know?” Dis Mon 2015;61(4):118.

- Hall W., Degenhardt, L. “Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use.” Lancet 2009;374(9698):1383.

- Huang, Y.H., et al. “An epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer: An update.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2015;24(1):15.

- Institute of Medicine; National Academy Press. “Marijuana and medicine: Assessing the science base.” Washington, D.C., 1999; (accessed, July, 2018).

- Lieberman, M.F. “Recredicinal marijuana.” American Journal of Opthalmology 2017 May;177:xv-xviii.

- Loflin, M., Earleywine, M. “A new method of cannabis ingestion: The dangers of dabs?” Addictive Behaviors 2014;39(10):1430.

- MacCoun R.J., Mello, M.M. “Half-baked — The retail promotion of marijuana edibles.” New England Journal of Medicine 2015;372(11):989.

- Mack, A., Joy, J. “Marijuana as Medicine? The Science Beyond the Controversy.” Washington (DC): 2000 National Academies Press (U.S.).

- Manrique-garcia, E., et al. “Cannabis, psychosis, and mortality: A cohort study of 50,373 Swedish Men.” American Journal of Psychiatry 2016;173(8):790.

- McLaren, J., et al. “Cannabis potency and contamination: A review of the literature.” Addiction 2008;103(7):1100.

- Medicinal Marijuana Association

- Mehmedic, Z., et al. “Potency trends of Δ9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993-2008.” Journal of Forensic Science.2010;55(5):1209.

- Meier, M.H., et al. “Associations between cannabis use and physical health problems in early midlife: A longitudinal comparison of persistent cannabis versus tobacco users. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73(7):731.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research.” Washington (DC): National Academies Press (U.S.); 2017.

- Nelson, B. “Cannabis conundrum: Evidence of harm?: Opposition to marijuana use is often rooted in arguments about the drug’s harm to children and adults, but the scientific evidence is seldom clear-cut.” Cancer Cytopathology 2015;123(1):1-2.

- “NIH research on marijuana and cannabinoids.” (accessed July, 2018).

- Peacock, A., et al. “Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use: 2017 status report.” Addiction. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1111/add.14234. [Epub ahead of print]

- Raber, J.C., et al. “Understanding dabs: Contamination concerns of cannabis concentrates and cannabinoid transfer during the act of dabbing.” Journey of Toxicological Science 2015;40(6):797.

- Roehr, B. “Review fails to advise on cannabis use because of poor research.” BMJ 2017;356:j248.

- Stockings, E., et al. “Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic non-cancer pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies.” Pain 2018 May 25. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001293. [Epub ahead of print]

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research, 2017” http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpinews/newsitem.aspx?RecordID=24625 (accessed July, 2018)

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. “Exposing the myth of smoked medical marijuana” (accessed, July, 2018).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. “Why does cannabis potency matter?” World Drug Report 2009 Series; (accessed July, 2018).

- U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators, The State of U.S. Health, 1990-2016: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among U.S. states. JAMA 2018;319(14):1444.

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, “Cannabis Eradication.”

- Walker, E.R., et al. “Excess mortality among people who report lifetime use of illegal drugs in the United States: A 20-year follow-up of a nationally representative survey.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2017;171:31.

- Whiting, P.F., et al. “Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of the American Medical Association 2015;313(24):2456.

Lingard Ellis - 2009

I was told I had mild emphysema. I was shocked, I had only had minor breathing problems at times. However I had smoked for 17 years when I was very young and had quit over 38 years ago, when I developed asthma. I always heard your lungs were cleared 5 years after you quit smoking, but they don’t tell you the damage is already done! Mild is not mild, I am on oxygen all the time.my son purchased herbal remedy for emphysema from solution health herbal clinic, which I used for 15 weeks and am totally Emphysema free. http://www.solutionhealthherbalclinic.com

Reply