Sugar buzz

The human desire for sugar appears unlimited. Latest figures show Americans consume about 152 pounds of sugar per year, per person, or about 3 pounds (6 cups) of sugar per person per week. OUCH!

The desire to exchange added sugar in foods for low- or zero-calorie versions might be a healthy option, if it prevented consumption of the large quantities of added sugar found in “regular” sodas and fruit drinks. But evidence mounts that many artificially sweetened beverages deliver their own negative effects, such as increased risk of type 2 diabetes, weight gain, heart disease, and stroke.

The desire to exchange added sugar in foods for low- or zero-calorie versions might be a healthy option, if it prevented consumption of the large quantities of added sugar found in “regular” sodas and fruit drinks. But evidence mounts that many artificially sweetened beverages deliver their own negative effects, such as increased risk of type 2 diabetes, weight gain, heart disease, and stroke.

The different types of sweeteners include low-calorie sweeteners (LCS) and a host of other non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS), also referred to as noncaloric sweeteners, intense sweeteners, or artificial sweeteners (AS). Artificial sweeteners derive through the manufacturing of plant extracts; they also are chemically processed from other products. Over the past few decades, there has been an alarming surge in the use of these items – with some 6,000 products on the market in the United States. About 25 percent of children and more than 41 percent of American adults report consuming foods and beverages containing AS. These numbers represent a 200-percent increase in consumption for children and a 54-percent jump for adults. But since AS levels are not required to be disclosed on food labels in the U.S., it is difficult to really know precisely how much AS we actually consume.

Types of sweeteners

Six different types of sweeteners appear in foods and beverages.

Sugars Carbohydrates found naturally in different foods including fruit, vegetables, cereals, and milk. The most common sugars include Sucrose, Glucose Dextrose, Fructose, Lactose, Maltose, Galactose, and Trehalose. I discussed sugars in a 2014 Health Yourself column, “You’re Sweet Enough Already.”

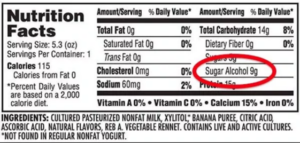

Sugar alcohols Natural carbohydrates found in small amounts in plants and some cereals. The most common sugar alcohols are Sorbitol, Xylitol, Mannitol, Maltitol, Erythritol, Isomalt, Lactitol, and Glycerol.

Sugar alcohols Natural carbohydrates found in small amounts in plants and some cereals. The most common sugar alcohols are Sorbitol, Xylitol, Mannitol, Maltitol, Erythritol, Isomalt, Lactitol, and Glycerol.

Natural caloric sweeteners Honey, maple syrup, sorghum syrup, and coconut and palm sugar.

Modified sugars Sugars produced by converting starch-using enzymes. Often used in cooking or in processed foods. Common modified sugars include high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), refined caramel syrup, inverted sugar, and golden syrup.

Natural zero-calorie sweeteners Natural, noncarbohydrate substance with little or no calories. Includes Luo Han Guo, a plant native to Southwestern China known as Monk Fruit; Stevia, extracted from the leaves of the plant species Stevia Rebaudiana native to Brazil and Paraguay; Thaumatin, a mixture of proteins isolated from the Katemfe fruit of West Africa; Pentadin, a sweet-tasting protein discovered and isolated in 1989 from the African tropical fruit Oubli; and Monellin, a sweet protein found in the fruit of the Serendipity Berry, native to Central and West Africa.

Artificial sweeteners Laboratory produced from different organic or inorganic products. Includes Aspartame, Sucralose, Saccharin, Neotame, Acesulfame K, and Cyclamate. These comprise the fastest-growing segment of the sweetener market.

Measuring sweetness

Measuring sweetness is not easy. There is considerable consistency among people rating “how sweet” a specific product may be when compared to a standard. However, there are large inconsistencies in ratings when a sweetener is placed in different products, such as soda, hard candy, or cake icing.

The oldest and most commonly used sweetness rating compares the perceived sweetness taste of an unknown sample relative to the sweetness taste of a chosen standard in a known solution (e.g. water). Sucrose (common table sugar) is used as the common sweetness standard and arbitrarily assigned a score of a 1.0. All other sweeteners are then rated either as more (fructose = 1.1-1.8, Aspartame = 180) or less (maltose = 0.4, lactose = 0.4) sweet, compared to the same quantity of sucrose.

| Artificial Sweeteners | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweetener | FDA Approved | Sweetness Index | Brand Name(s) and Common Uses |

| Acesulfame-K (E950*) | 1988 | 200x | Sunett®, Sweet One® – Soft drinks, baked goods, gum, gelatin |

| Advantame (E969) | 2014 | 20,000x | No consumer product |

| Aspartame (E951) | 1981 | 180x | NutraSweet®, Equal® – Gum, diet soda, instant tea/coffee, yogurt, pudding |

| Neotame (E961) | 2002 | 7,000x | No consumer product, mostly by food producers |

| Saccharin (E954) | 1879 | 300-400x | Sweet ’N Low®, Sweet Twin, Sugar Twin® – Soft drinks, candy, medicine, toothpaste, lip gloss, baked goods, salad dressing |

| Stevia (E960) | 2008 | 200x | TruviaTM, PureViaTM, Sun Crystals® – Baked goods, soft drinks |

| Sucralose (E955) | 1998 | 600x | Splenda® – Baked goods |

| Cyclamate (E952) | 1937 | 30-50x | Banned in the U.S., 1970 |

| Source: Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2006; Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 2011. * International Numbering System (INS) for food additives, [i.e. 961 in the US; the E in front of the number is the corresponding EU numbers (i.e. E961)] |

|||

Most artificial sweeteners were discovered by accident

Saccharin, the oldest artificial sweetener, was discovered in 1879 by scientists researching new uses for coal-tar derivatives. After touching some of the substances, one scientist forgot to wash his hands and tasted something sweet on his fingers. After tasting everything in the lab, he figured out it was benzoic sulfimide, a coal tar derivative that turns out to be about 300x times sweeter than sugar. Four years later he patented the product and called it Saccharin (the Latin word for sugary). The rest is history – he became fantastically wealthy and gave no credit to his partner or their institution. [Did you know that Monsanto got its start in 1901 selling saccharin.]

Cyclamate was discovered in 1937 when a scientist who was developing an anti-fever medication spilled some of it on his hands and noticed the sweet taste. It was not as sweet as Saccharin, but it was less bitter. By 1968 Americans were consuming more than 17 million pounds of the stuff each year. That halted when it was shown to cause bladder cancer in rats, resulting in an immediate FDA ban. It’s still used in many other countries.

Cyclamate was discovered in 1937 when a scientist who was developing an anti-fever medication spilled some of it on his hands and noticed the sweet taste. It was not as sweet as Saccharin, but it was less bitter. By 1968 Americans were consuming more than 17 million pounds of the stuff each year. That halted when it was shown to cause bladder cancer in rats, resulting in an immediate FDA ban. It’s still used in many other countries.

Aspartame also was discovered by accident in 1965 by a chemist working on an anti-ulcer drug who accidentally ingested some of the substance and noticed the sweet taste. He went on to develop the product for commercial use. In 1974, production halted after FDA approval was paused due to claims that it caused brain tumors in rodents. The sweetener finally hit the market in 1981 as Nutrasweet. With aggressive marketing, aspartame replaced more than a billion pounds of sugar in the American diet during the 1980s. Diet Coke, made with aspartame, was launched during this time.

Acesulfame K was discovered in 1967 by a chemist who after accidentally dipping his fingers into the chemicals put his fingers in his mouth. When he noticed the sweet taste, he preceded to isolate the compound and test it as an AS on the market.

The next great artificial sweetener breakthrough occurred in 1976 in England. An Indian graduate student was investigating a way to bond sucrose to chlorine as an intermediate in the production of an insecticide. (Seriously.) The student’s supervisor asked him to “test” the compound, but because of his poor English, he misunderstood it as a request to “taste” the compound. He did so and lived to report the sweetness. The result was Splenda, which has replaced NutraSweet as the most widely consumed AS on the market.

Safety

Some AS products appear to be safer than others; some appear to be totally safe for certain people but cause severe reactions in others. Animal testing is not always helpful. Since AS are incredibly sweet (see table), only small quantities are needed. Unfortunately, animals testing involves feeding animals large quantities over prolonged time periods to simulate human over-use. These tests are cruel and inhumane to animals and detrimental to their health. Moreover, research results with animals often do not translate to humans. While there are numerous intervention studies with humans, they are difficult to complete for long periods of time. Often the subjects withdraw from the study due to the nauseating effects of the intense sweetness.

Below I summarize the latest research regarding the safety of various artificial sweeteners.

Acesulfame-K

Results are mixed. A 2005 study showed no evidence of cancer activity in rats, while a 2008 animal study showed long-term use encouraged development of urinary tract tumors. Acesulfame-K consists of a potassium salt containing methylene chloride, a known carcinogen. Reported side effects of long-term exposure to methylene chloride include nausea, headaches, mood problems, hypoglycemia, liver and kidney impairment, eyesight problems, and possibly cancer. Large doses of acetoacetamide, a breakdown product of acesulfame-K, are known to affect thyroid function in laboratory animals, mainly rats, rabbits, and dogs. Of all artificial sweeteners, acesulfame-K has undergone the least scientific scrutiny. The Center for Science in the Public Interest states that acesulfame-K can be potentially dangerous and should be avoided.

Advantame

The Center for Science in the Public Interest points to an alarming concern regarding the FDA’s evaluation of advantame. They state: “…an initial concern is that in a key cancer study in mice, the number of mice that survived to the end of the study was below FDA’s own scientific recommendations, and, is therefore inadequate to provide confidence in the safety of a chemical likely to be consumed by millions of people.” Also, individuals with the rare genetic disorder phenylketonuria (PKU) should avoid advantame since it contains phenylalanine, which PKU patients cannot metabolize.

Aspartame

There are more FDA adverse-reaction reports for aspartame, including death, than for all other food additives combined. There are more than 900 published studies on the health hazards of aspartame. For many people, aspartame can act as a food trigger for migraines. The Center for Science in the Public Interest reports aspartame can cause neurological problems, and that consumption over extended periods of time can increase cancer risks in some people. Commonly reported side effects include headaches, change in mood, change in vision, convulsions and seizures, sleep problems/insomnia, change in heart rate, hallucination, abdominal cramps/pain, memory loss, rash, nausea and vomiting, fatigue and weakness, dizziness/poor equilibrium, diarrhea, hives, and joint pain. Despite these adverse reports, the weight of existing scientific evidence indicates that aspartame is safe at current levels of use.

Neotame

One of only two artificial sweeteners ranked as “safe” by the Center for Science in the Public Interest. The main issue with Neotame seems to be guilt by association, because it is a chemical derivative of aspartame. There have been no reported side effects from Neotame. Because of the tiny amount needed it is not required to be named in a product’s list of ingredients. Unless new information arises, it appears to be safe.

Saccharin

Has an unpleasant, bitter aftertaste, thus, it is often mixed with other low- or zero-calorie sweeteners. In the 1970s, several studies linked saccharin to the development of bladder cancer in rats, and it was then classified as “possibly cancerous to humans.” Further research, however, discovered that cancer development did not apply to humans. Due to the lack of solid evidence linking saccharin to cancer development, its classification was changed to “not classifiable as cancerous to humans.”

Stevia

Stevia products are considered safe, even for those with diabetes who are pregnant. More research needs to be done to provide conclusive evidence on weight management, diabetes, and other health issues.

Sucralose

A recent summary review concluded that sucralose, taken in moderate amounts, is safe for humans. Reported side effects, although not consistent, include increased onset of migraine headaches, muscle aches, stomach cramps and diarrhea, bladder issues, skin irritation, dizziness and inflammation, shrinking of the thymus gland, and liver and kidney dysfunction. Also, a recent study found sucralose reduced healthy intestinal bacteria, which are needed for proper digestion.

Cyclamate

Cyclamate was used in the U.S. in diet foods until 1970, at which time it was banned. Tests showed that rodents and primates fed large quantities over a prolonged period had an increased rate of tumor development. Cyclamate is approved in almost every other country. It has been used for about 70 years and despite the fears, no side effects have been reported in humans. It is now believed not to cause cancer directly.

Summary

Mounting evidence reveals that AS beverages could have their own adverse health effects, including stroke. A recent, comprehensive study that analyzed data on AS-soda consumption in 81,714 women age 50 and older contributes to this growing suspicion. This latest study found that those who regularly drank two or more 12-ounce cans of AS soda per day had a tremendous increase in risk of stroke. After adjusting for known stroke-risk factors, such as obesity, age, and high blood pressure, the women who drank 24 ounces or more of diet beverages per day were 23-percent more likely to have a stroke than those who drank less than 12 ounces per day. They also were 29-percent more likely to develop heart disease and 16-percent more likely to die from any cause. Another study found that people, males and females age 45 and older who drank one or more diet soda every day, were three times more likely to have a stroke than those who didn’t drink them.

Mounting evidence reveals that AS beverages could have their own adverse health effects, including stroke. A recent, comprehensive study that analyzed data on AS-soda consumption in 81,714 women age 50 and older contributes to this growing suspicion. This latest study found that those who regularly drank two or more 12-ounce cans of AS soda per day had a tremendous increase in risk of stroke. After adjusting for known stroke-risk factors, such as obesity, age, and high blood pressure, the women who drank 24 ounces or more of diet beverages per day were 23-percent more likely to have a stroke than those who drank less than 12 ounces per day. They also were 29-percent more likely to develop heart disease and 16-percent more likely to die from any cause. Another study found that people, males and females age 45 and older who drank one or more diet soda every day, were three times more likely to have a stroke than those who didn’t drink them.

Drink to your health

The best advice, it seems to me, is to err on the side of caution and try not to consume AS-laced products. If you want to drink AS sodas to wean off sugar-sweetened ones, you should do so for a limited time period to transition to healthier beverages. I recommend WATER!

Water provides everything the body needs to restore fluids lost through metabolism, breathing, sweating, and the removal of waste. It’s the perfect beverage for quenching thirst and for rehydration. To spice up your daily water intake, try adding citrus zest (lemon, lime, orange, grapefruit), crushed fresh mint, peeled/sliced fresh ginger, sliced cucumbers, or even crushed berries to a cold glass or pitcher of water.

References

- Borges, M.C., et al. 2017. “Artificially sweetened beverages and the response to the global obesity crisis.” PLoS Medicine; 14(1):e1002195.

- Danika, M., et al. 2018. “Low-/no-calorie sweeteners: A review of global intakes” Nutrients; 10(3):357.

- Johnson, R.K., et al. 2018. American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Stroke Council. “Low-calorie sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health: A science advisory from the American Heart Association.” Circulation; 28;138(9):e126.

- Mossavar-Rahmani, Y., et al. 2019. “Artificially sweetened beverages and stroke, coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality in the women’s health initiative.” Stroke; 50:00-00. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023100.

- Pase, M.P., et al. 2017. “Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: A prospective cohort study.” Stroke; 48(7):2013.

- Pearlman, M., et al. 2017. “The association between artificial sweeteners and obesity.” Current Gastroenterology Reports ;19:64.

- Suez, J., et al. 2015. “Noncaloric artificial sweeteners and the microbiome: Findings and challenges.” Gut Microbes; 6:149.

- Wersching, H., et al. 2017. “Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia: Are soft drinks hard on the brain?” Stroke; 48:1129.

- Yang, Q., 2010. “Gain weight by ‘going diet?’ Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine; 83(2):101.

Robert Lee - Medical School 1979

A eye opening review of an overlooked aspect of your health. Worthy of much broader dissemination.

Reply

Sandy Moore - 2001

So tell me then, why visitors to the U of M hospitals are not allowed to choose between sodas sweetened with sugar and sodas sweetened with all these unhealthy sugar replacement options? Only diet sodas are available for purchase, which given the evidence, is terrible too. Ideally we would only consume soft drinks on special occasions if ever, but since so many love these beverages on a daily basis (my spouse included), shouldn’t adults be allowed to pick their poison?

Reply