That ‘mysterious’ film…

(MGM, 1968)

Most breakthrough films arrive on the silver screen after complex journeys fraught with creative and financial travail.

New York crime bosses founded the Italian-American Civil Rights League as an organized effort to fight against the making of The Godfather (1972), for example. Meanwhile, Paramount executives wrote off cinematographer Gordon Willis’ low-key, noir lighting as unpleasantly murky; editor Aram Avakian complained that “the film cuts together like a Chinese jigsaw puzzle”; and, at just 29 years old, director Francis Ford Coppola lived in daily fear he would be fired.

It’s hard to believe now, but filmmaker George Lucas struggled with technical-effects issues brought on in part by a skeptical production crew that thought his neo-space opera Star Wars (1977) was pure “folly.”

In addition, critics, filmgoers, and Warner Bros. executives initially were turned off by the slow pace and narrative complexities of Blade Runner (1982). Ridley Scott’s neo-sci-fi film evolved over several iterations and would have to find its cult status by way of video rentals and DVD distribution. The first version of the film in which director Scott exercised full artistic control didn’t come until 2007 when a digitally remastered version of Blade Runner arrived for the film’s 25th anniversary.

The big bang

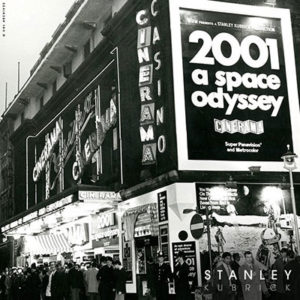

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) hit screens before any of these three epic films, and arrived in theaters as the most complex and challenging motion picture made to date. The film — funded by MGM — contained more than 200 special-effects scenes, a remarkable achievement in the pre-digital era. Director Stanley Kubrick, a meticulous and brilliant filmmaker (some said “despotic”), held the reins of 2001’s making from beginning to end. During its creation, he demanded, and won, absolute secrecy — no production stills or other pre-release publicity existed. Outsiders not privy to what was happening on Kubrick’s soundstages referred to the project as “that mysterious film.” Even the picture’s working titles gave scant hint of its content: Gift from the Stars and Journey Beyond the Stars.

A deeply paranoid Kubrick obsessed about other filmmakers stealing his conceptual content and complex production designs. But when publicity and marketing executives at MGM griped about the director’s obstinate secrecy, studio president and CEO Robert O’Brien warned: “Leave Kubrick alone.” Thus, the auteur effectively avoided the end-game executive meddling that would befall The Godfather and Blade Runner; and while 2001 generated numerous crew concerns about the ins-and-outs of creating Kubrick’s expansive space odyssey, none called it a “folly” as would happen with Star Wars. Many did become unduly stressed, however, as they worked against tremendous odds to finish the film on time. Alas, they wouldn’t.

Now, 50 years since the premiere of 2001: A Space Odyssey, comes a compelling book about the four-year period (1964-68) during which it was made. I’ll say up front that the book is by far the best, most informative, and engaging account of the production of an artistically complex motion picture I’ve ever read. Author Michael Benson’s Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece (Simon & Schuster, 2018) embraces the unextractable collaboration between a visionary filmmaker and a brilliant writer who helped define science fiction’s golden age. Benson’s detailed book employs a chronological structure as it follows 2001’s creation from conception to controversial release, concluding with an overview of the movie’s storied aftermath. Young filmgoers gravitated toward 2001’s cryptic meanings and surrealistic imagery with a passion while older audiences often responded with catcalls and walkouts.

Conception

Thirty-six-year-old Kubrick, riding high on the much-heralded critical and popular success of his satire Dr. Strangelove (1964), turned immediately to the development of a space adventure that would span time from “the dawn of man” to the year 2001, when a lunar team discovers a black monolith on the moon’s surface. In space narratives, monoliths are machines built by an unseen extraterrestrial species. In 1964, Kubrick began lengthy development sessions with futurist author Clarke, best known for two classics: Childhood’s End (1953) and The City and The Stars (1956). Clarke’s novelette The Sentinel (1948) served as 2001’s basic starting point. Hollywood optioned five other space stories by Clarke as the screenplay developed. Interestingly, these sci-fi narratives were fashioned by Kubrick and Clarke into a fictional novel, to serve as a production guide for publication at the time of 2001’s release. Kubrick worked closely with Clarke in this unusual development process, telling him, “If you can describe it, I can film it.” (p.70)

Benson’s book offers a vivid passage from the novel version that suggests how Kubrick’s special-effects team transmuted Clarke’s prose into filmic imagery:

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine, 1968. (Wikipedia.)

“Now the turning wheels of light merged together and their spokes fused into luminous images that slowly receded into the distance. They split into pairs, and the resulting set of lines started to oscillate across each other, continually changing their angle of intersection. Fantastic fleeting geometric images flickered in and out of existence as the glowing grids meshed and unmeshed, and the humanoid watched from his metal cave — wide-eyed, slack-jawed, and wholly receptive.” (p.75)

In the pre-production stages, Kubrick embarked on expansive research, even exploring “mind” experiments conducted at the Massachusetts Mental Health Clinic by Dr. Walter Pahnkes. Kubrick wanted to know if any of Pahnkes’ subjects “had passed through a kind of Star Gate — a trip beyond the infinite.” (p.100) In 2001, effects artists rendered Star Gate as a lengthy, psychedelic event experienced by Commander Dave Bowman as he passed into Jupiter’s “infinite space.”

Moving abroad

In 1965, Kubrick relocated from New York City to England, thereafter making the U.K. his permanent home and workplace. In the U.K. he would continue to assemble an “impeccable” production and design team for shooting at Borehamwood (Elstree) and nearby Shepperton.

It’s at this point that Benson’s book comes to mesmerizing life. Every figure involved in the production — from Kubrick to tea-boy Andrew Burkin — is fleshed out by Benson with personal details that define each as a well-placed component in the making of 2001. Benson provides an engaging, anecdotal avenue to characterization as he chronicles the crew’s activities on and off the set. Especially notable are accounts of the cast and crew’s one-on-one interactions with Kubrick that most would later describe as “unique,” although they weren’t. Kubrick was simply a caring, congenial man.

Kubrick: A lighting genius

Benson’s rendering of Kubrick reveals a totally committed, fully focused artist with an uncanny knowledge of all aspects of filmmaking. The author includes numerous candid snapshots of Kubrick wandering the studio stages with a standard Polaroid camera. It was the director’s unusual method of using black-and-white, two-dimensional optics for final scrutiny of the lighting design. Some observers estimated that Kubrick took as many as 10,000 Polaroids. During shooting, cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, a 25-year film veteran, declared Kubrick a “lighting genius,” telling 2001 publicist Roger Caras: “He knows more about the mechanics of optics and the chemistry of photography than anybody who’s ever lived.” (p.176) Quite an accolade.

Creativity meets the mechanical

HAL’s red eye was a Nikon Nikkor 8mm wide-angle lens, lit from behind. (Wikipedia.)

Taken together, Benson’s richly detailed production and post-production chapters are essential reading for anyone interested in the complex relationship between film mechanics and film art. A key factor in Kubrick’s imagining of a “perfect,” fully realized space odyssey led him to incessantly tweak, shift, and refine aspects of 2001’s concept.

Kubrick faced countless self-imposed challenges, including the creation and mechanics of a rotating centrifuge set-piece, massive in size and complexity at 38 feet in diameter and weighing 30 tons. Similarly massive and costly was the development of a two-ton monolith set piece made from relatively new plexiglass material and painted black. The first monolith in 2001 appears in the “Dawn of Man” segment, discovered by a group of prehistoric humanoids. In addition, Kubrick and the actors struggled to find acceptable, believable resolutions to critical narrative intersections: the elimination of HAL, a computer with human consciousness; how to stage the deaths of Poole and Bowman; and how to realize Bowman’s climactic reincarnation as a Star Child. Also, adapting to the shooting of scenes on 65mm negative film for wide-screen Super Panavision proved tricky, resulting in flubs, mistakes, and costly reshoots.

Post-production

The concluding chapters of Benson’s book are compelling as they detail the integration of special effects into the main-unit scenes shot at Borehamwood. Led by 23-year-old Doug Trumbull, the effects process is depicted as a laborious and tedious undertaking that did not allow for errors or mishaps. And there were yet other demanding tasks: casting, costuming, choreographing, and filming 2001’s opening segment “The Dawn of Man” in the Namib Desert; installing sonic effects and the musical score — mainly classical works chosen from old vinyl LPs; and finally cutting and editing the footage — done almost entirely by Kubrick on a Movieola.

After the credits

There’s so much more to read, learn, and enjoy in Benson’s book than what I can describe here. Every chapter is superbly rendered. On its impact and historic import, Steven Spielberg is cited as proclaiming 2001: A Space Odyssey “the big bang” that inspired his generation of filmmakers. Here are a few other interesting facts from the book:

The 1968 opening. (Image: Stanley Kubrick via Twitter.)

- From 1950-60, feature-length, sci-fi releases grew from about three per year to more than 150, mostly B-grade productions.

- Kubrick’s three-point maxim for making a motion picture: “Was it interesting? Was it believable? Was it beautiful or aesthetically pleasing? At least two of these have to be in every shot.” (p. 92)

- There are fewer than 40 minutes of spoken dialogue in the film’s 2.5-hour running time.

- Computer HAL’s red eye was a Nikon Nikkor 8mm wide-angle lens, lit from behind.

- HAL — originally named Athena — was an acronym for “H/euristically programmed AL/gorithmic computer — suggested by Marvin Minsky of MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

- Kubrick significantly exceeded his original $5 million budget.

- Some of the most striking visual-effect techniques were realized by a passel of once-standard Bell and Howell 16mm projectors hidden out of view.

- 2001’s original running time of 161 minutes was trimmed to 142 minutes after unfavorable preview reactions.

- 2001’s production occurred at a time when NASA’s budget was at a peak.

- Lead actor Keir Dullea and Kubrick had an intense fear of flying; both traveled mainly by ship.

- Lead costume designer Hardy Amies was Queen Elizabeth II’s official dressmaker from the time of her coronation in 1952 until Amies’ retirement in 1989.

- Cast and crew filming at the huge Shepperton studios had to contend with dust, flies, and bats that flew into shots.

- 2001 overran its delivery date by two months.

- The last main unit scene — in a futuristic French hotel room — was shot in June 1966.

- The first full-length screening of 2001 took place on March 23, 1968, in Culver City, Calif., mainly for the benefit of MGM executives.

- New American Library purchased the novel version of 2001 in 1968 for $130,000. The book became a huge bestseller with 50-plus press printings.

Mark Garman - 1974 & 1978

Fall semester 1970, everyone in Chicago House of West Quad made their way to watch the film in the auditorium of Angell/Haven building. As the final sequence started, many members of the mesmerized audience rushed the stage to watch. Wild and fantastic.

Reply

Jerry Bilik

I loved the article, and “2001” is my absolute favorite film of all time – I lecture on it – not only from the musical standpoint, but from all the elements so perfectly assembled into a visual and aural masterpiece. And my favorite praise of the endeavor is Kubrick’s total avoidance of digital technology – I LOVE it!

Reply

Roger Williams - 1985

“HAL — originally named Athena — was an acronym for “H/euristically programmed AL/gorithmic computer — suggested by Marvin Minsky of MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.”

It has been noted that “HAL” is a one letter shift up using “IBM” as a base sequence…therefore one step above IBM. Not sure if this was intentional or happenstance. I’ve never seen a source which pins this done as true/false.

Reply

Mark Seibold - 1972

A close friend of mine since early grade school, had asked me to go see the new 2001: A Space Odyssey film at the Hollywood Theater in our home town of Portland Oregon, in the late summer of 1968. I just purchased my first astronomy telescope less than a year before. We were both avid young amateur astronomers. I was enthralled with the close up the pictures of the planet Jupiter and its moons toward the latter sequence of the film, because I was familiar with observing the planet through my telescope for lengths of time. I’d become so involved with observations through my telescope that I began losing interest in popular commercial American television. I had previously been building Crystal radios since age 10, when neighbors sold me an antique Zenith Transoceanic shortwave radio. I soon discovered the BBC and lost interest in popular American commercialized radio. The only American TV show I continued to watch after 1965 was The Avengers from England.

So Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 don’t run into place as a logical occurrence in my life. And still today it’s my favorite motion picture of all time. I would go on to teach as an adjunct professor of astronomy an evening course in a local University by age 50 in the Autumn of 2004. I soon was producing large technical pastel sketches from the observations through my larger telescope, as these sketches eventually appeared in NASA website often. I also spoke about this on national public radio’s Talk of the Nation program several times. Although I lost all interest in American television, I eventually became a background extra actor on Hollywood movie sets for the past 20 years of my life

Reply