High-intensity interval training

Scientists have been interested in the use of exercise as adjunctive therapy since the turn of the last century. However, the amount and rigor of research was generally unremarkable and limited in breadth and depth. But since the 1950s and ’60s, experts began to develop more structure within the discipline of exercise science (Kinesiology), and scientists, properly trained in the field, began to shift their focus toward the role of exercise as medicine.

Some of the more persistent issues to arise from the burgeoning literature on exercise and health center on questions of duration (amount of time), intensity (how hard) and the type (mode) of exercise, and how each positively or negatively influence health. (See “Responders vs. nonresponders,” Health Yourself, April 2015.)

Understanding how (1) duration, (2) intensity and (3) type of exercise confer health benefits takes on current importance since the majority of the U.S. adult population fails to meet recommended physical activity guidelines for general fitness and health. A primary reason cited for this failure to exercise regularly is a perceived lack of time.

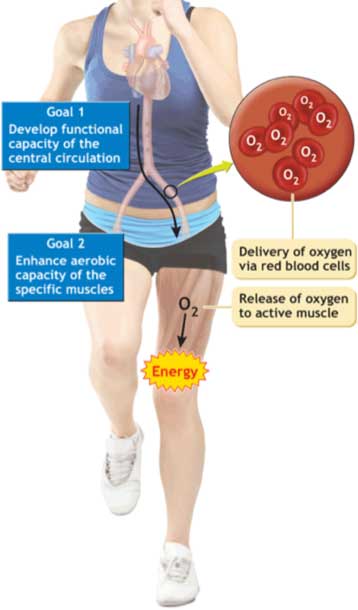

Research reveals that to improve cardiovascular health, exercise must include sufficient cardiovascular demands to reach an intensity to increase (overload) overall work of the heart. This includes how much blood the heart can pump per stroke (stroke volume) and the total amount of blood pumped per minute (cardiac output). It also includes activating muscle groups to enhance local circulation and the muscle’s “metabolic machinery.” These physiological components are measured as the greatest amount of oxygen a person can consume per minute, termed aerobic capacity.

The figure at right illustrates these two major goals of “aerobic” exercise training. Research shows that both relatively brief bouts of repeated activity, as well as efforts of long, continuous, duration can enhance aerobic capacity, as long as the activity attains sufficient intensity to overload the different systems.

The figure at right illustrates these two major goals of “aerobic” exercise training. Research shows that both relatively brief bouts of repeated activity, as well as efforts of long, continuous, duration can enhance aerobic capacity, as long as the activity attains sufficient intensity to overload the different systems.

HIIT — High-intensity interval training

HIIT involves repeated high-intensity bouts of activity with brief rest or low-intensity relief intervals. Typically, the exercise duration can vary from a few seconds to several minutes (or longer), depending on the desired training outcome. With correct spacing of exercise and relief (rest) intervals, one can perform extraordinary amounts of intense activity, not normally possible if activity progressed continuously, nonstop.

Here is an example of performing a large volume of intense exercise during a HIIT workout. Few people can maintain a 4-minute-mile pace for longer than 1 minute, let alone complete a mile in 4 minutes. Suppose running intervals were limited to only 10 seconds followed by a 30-second recovery. This scenario makes it reasonably easy to maintain the exercise-to-relief intervals and complete the mile in 4 minutes of actual running. This does not parallel a world-class performance but illustrates that a person can accomplish a considerable quantity of normally exhausting activity when spacing the exercise-to-relief interval at a proper pace. This strategy of intense training interspersed with relief intervals can apply to any type of exercise, including treadmill, stair climbing, and bicycle exercise. It even works with weight training.

A proper HIIT prescription evolves from four considerations: (1) intensity, (2) duration interval, (3) length of recovery (relief) interval, and (4) number of repetitions of the exercise-to-relief interval.

HIFT is a variant of HIIT. High-intensity functional training emphasizes multi-joint movements using bodyweight as the resistance. Functional training can be modified to any fitness level to enhance muscle recruitment. Exercises and activity durations vary constantly and may or may not incorporate rest.

Popular movement

Recently, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) surveyed more than 4,000 fitness professionals, and the results indicate that HIIT forecasts as the year’s most popular fitness trend. Since 2014 HIIT training has steadily become more and more popular.

TOP TEN FITNESS TRENDS FOR 2018

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT)

- Group training

- Wearable technology

- Bodyweight training

- Strength training

- Yoga

- Personal training

- Fitness programs for older adults

- Functional fitness

- Educated and experienced fitness professionals

HIIT rationale

Interval training regimens have a sound basis in physiology and energy metabolism. In the example of the HIIT 4-minute-mile run, repeated 10-second exercise bouts permit completion of intense exercise without appreciable development of metabolic fatigue that would occur during longer duration exercise.

With HIIT training the relief interval is either passive (rest–relief) or active (work–relief). A ratio of exercise duration to recovery duration usually formulates the duration of the relief interval. Different exercise-to-relief intervals are used depending on the desired outcome. The optimal exercise-to-relief interval ratio usually is 1:1 or 1:1.5 to train the aerobic energy system (see section below). This exercise-to-relief interval ensures that cardiovascular and aerobic metabolic stress attain near peak levels with the repeated but relatively short exercise intervals. The duration of the rest interval takes on less importance with longer periods of intermittent exercise because sufficient time exists for the body to adjust metabolic and circulatory parameters during the activity.

HIIT’s health benefits

Varying the speed and incline on a treadmill is a great way to bring HIIT into your routine. (Image: iStock photo.)

Compared with traditional moderate-intensity, continuous training (MICT), HIIT represents a potent and time-efficient strategy for eliciting improvements in parameters of cardiovascular health. This is true even in patients with cardiovascular disease, and leads to greater or comparable improvements in such parameters as insulin sensitivity and blood pressure.

While the lay media promotes HIIT as a superior and time-efficient method for fat loss, the research is equivocal, with large variations in study design. Few studies directly compare interval training protocols with MICT or use a valid assessment of body fat. It is therefore unclear whether interval training is a suitable alternative or substitute for the more time-consuming MICT. It remains to be see which of the two approaches is best for fat loss.

In one example, researchers studied several groups of volunteers consisting of sedentary but healthy middle-aged men and women. Another group was composed of middle-age and older patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Initial testing quantified their maximum heart rate and peak power output on a stationary bicycle. These values were low. Participants then trained using repetitive bouts of short bursts of HIIT training. This routine involved 1-minute exercise bouts at about 90 percent of maximum heart rate followed by 1 minute of easy recovery with 10 total intervals of activity and recovery. The total workout lasted 20 minutes. Participants, particularly the cardiac patients, significantly improved overall health and cardiovascular fitness. The interesting finding was that all participants embraced the routine despite the fact that their ratings of perceived exertion during each exercise bout was 7 or higher on a 10-point scale.

Quick, convenient and efficient

HIIT can be done anywhere: at home, in a hotel room, in a park, at a gym. Most routines can be completed in 30 minutes or less. In addition, a HIFT workout can be designed to not require any equipment, only your body weight. In these workouts, the focus is on increasing the heart rate and keeping it up for short bursts of activity — and repeating the sequence over and over.

All you need to do is choose the exercise intensity, the total time you want to exercise, and the exercise-to-relief interval.

If you are a first-timer choose a low-to-moderate intensity until you are accustomed to performing the exercise at a higher rate. Thereafter, increase the intensity systematically. The goal is to exercise to an intensity that approaches your maximum perceived capacity (maybe 80-to-90 percent of max).

For those who like walking and/or running, a good starter workout would be to walk or run at a fast pace for 1 minute and then walk or run for 2 minutes at a leisurely pace. Repeat that 3-minute interval five times for a 15-minute workout.

A more involved HIIT workout could include almost any type of movement/exercise, with or without equipment. For example, many HIIT and HIFT workouts include such tasks as simulating jab-boxing, push-ups, sit-ups, simulating or real stair-stepping, chair dips, arm circles, etc. Anything is possible and appropriate.

Next, choose the exercise-to-relief interval. Here is a typical exercise-to-rest interval progression.

• Week 1: 30 seconds of exercise / 60-second rest

• Week 2: 30 seconds of exercise / 45-second rest

• Week 3: 30 seconds of exercise / 30-second rest

• Week 4: 45 seconds of exercise / 30-second rest

References

- Campbell, W.W., et al. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2019. “High-intensity interval training for cardiometabolic disease prevention.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise; 51(6):1220.

- Faelli, E., et al. 2019. “Effects of two high-intensity interval training concepts in recreational runners.” International Journal of Sports Medicine. Aug 2. doi: 10.1055/a-0964-0155. [Epub ahead of print].

- Feito, Y.,et al. 2018. “High-intensity functional training (HIFT): Definition and research implications for improved fitness.” Sports (Basel);6(3). pii: E76. doi: 10.3390/sports6030076.

- Gibala, M.J., et al. “Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease.” The Journal of Physiology; 590:1077.

- Hood, M.S., et al. 2011. “Low-volume interval training improves muscle oxidative capacity in sedentary adults.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise; 43:1849.

- Keating, S.E., et al. 2017. “A systematic review and meta-analysis of interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on body adiposity.” Obesity Reviews; 18(8):943.

- Lira, F.S., et al. 2019. “Impact of 5-week high-intensity interval training on indices of cardiometabolic health in men.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity; 13(2):1359.

- Shiraev, T., Barclay, G. 2012. “Evidence based exercise-clinical benefits of high intensity interval training.” Australian Family Physician; 41(12):960-2.

- Thompson, W. 2017. “Worldwide survey of fitness trends for 2018: The CREP edition.” ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal; 21(6):10.