The milkman cometh

In the U.S., health experts recommend adults and children 9 years of age or older consume an average of three 8 oz. servings (237 mL) of milk daily (or equivalent cheese, yogurt, or other dairy product). This amount is substantially higher than the current average adult intake of only 1.6 calcium servings daily.

Scientists supposedly have justified this relatively high recommendation to meet to reduce bone fractures and all-cause mortality risk. But recently scientists have challenged this assertion about milk’s health benefits and warned about possible adverse health outcomes.

Dairy product composition

The table below presents the nutrient composition of human milk, cow’s milk, and cheese. To increase milk production, cows have been bred to produce higher insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) levels. This increases the level of progestins and estrogens in their milk.

| Human and Cow’s Milk and Cheese Nutrient Composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Human milk, 8oz | Whole-fat cow’s milk, 8oz | Fat-free cow’s milk, 8oz | Cheddar cheese, 37g (equals 8oz whole-fat cow’s milk) |

| Calories | 172 | 149 | 83 | 149 |

| Protein, g | 2.5 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 8 |

| Total fat, g | 10 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 12.3 |

| Saturated fat, g | 4.9 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 7 |

| Carbohydrate, g | 16.9 | 11.7 | 12.1 | 1.1 |

| Calcium, mg | 78 | 276 | 298 | 262 |

| Potassium, mg | 125 | 322 | 381 | 28 |

| Phosphorus, mg | 34.4 | 205 | 246 | 16.79 |

| Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture. | ||||

Milk processing has many potential positive and negative health implications. For example, pasteurization reduces brucellosis, an infectious disease characterized by high- and low-fever swings, the sweats, muscle and joint pains, weakness, tuberculosis, and other pathogen transmissions. In contrast, fermentation, used to produce aged cheese, yogurt, kefir, and other products, denatures important peptide-hormones. The process alters protein antigens (a toxin or other foreign substance which induces an immune response in the body, especially the production of antibodies), reduces lactose content, and affects bacterial composition.

Milk and bone health

Elsie the Cow first appeared in 1936 as a mascot for the Borden Dairy Company to symbolize the “perfect dairy product.”

Experts often cite calcium’s supposed bone-health benefits as a way to rationalize this recommended high level of lifelong milk consumption. Such an assumption derives from early studies assessing calcium balance in just 155 adults in whom the estimated daily calcium intake necessary to maintain calcium balance averaged only 741 mg. These small studies had other serious limitations, including short duration (2-3 weeks) and varying habitual calcium intakes. In other studies, the threshold for estimated calcium balance occurred at approximately 200 mg per day among males who had low habitual calcium intakes.

In randomized trials that used bone mineral density as a fracture risk indicator, daily calcium supplements of 1,000-2,000 mg produced a 1-3-percent greater bone mineral density (BMD) than a placebo. If sustained, this small divergence would be important. However, after one year, the rate of BMD change among late perimenopausal and postmenopausal women equaled the placebo value, and upon discontinuing the supplementation, the small difference in BMD disappeared. Because of this transient “beneficial effect” of calcium supplementation, trials lasting one year or less can be misleading, and the 2-3-week balance studies to establish calcium requirements have limited relevance to fracture risk. In fact, higher calcium intakes may relate to higher hip fracture rates.

The figure below shows milk consumption as a proportion of total energy intake versus age-standardized hip fracture rates annually per 100,000 persons. As can be observed, countries with the highest milk and calcium intakes tend to have the highest hip fracture rates. This positive association may not be causal, however, because confounding factors like vitamin D status and ethnicity could have impacted the findings.

Data on national milk intake (including all forms of milk, cheese, and other derived products) come from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization report on Milk and Dairy Products in Human Nutrition, and nationally representative hip fracture rates combining males and females standardized to the 2010 world population.

Low dairy consumption tracks with low hip-fracture rates across diverse cultures, climates, and economic status. Note that Indonesia and China rank poorly for milk intake yet have the lowest yearly bone fracture rates. To confound the issue, some countries with relatively high dairy consumption also have relatively low hip-fracture rates. The U.S., Australia, and France, for example, experience relatively low fracture rates with only moderate milk consumption. Nevertheless, the trend for increased dairy intake to associate with increased hip-fracture risk seems clear.

Milk consumption and mortality

Specialty products, like the dairy alternative oat “milk,” retail for a higher price than cow’s milk.

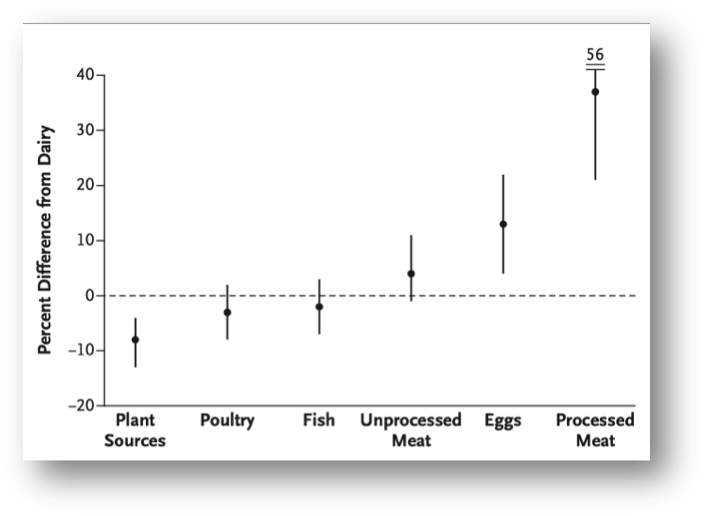

When comparing major protein sources from animals or plants, dairy consumption associates with lower mortality than with processed red meat and egg consumption. Similar mortality occurs for unprocessed red meat, poultry, and fish consumption, yet significantly higher than the consumption of plant-based protein sources. This figure shows the percent difference in all-cause mortality associated with protein sources. The dashed line at 0 is the reference mortality value associated with major protein dairy sources.

Comparisons reflect 3 percent of protein-energy from each source, with milk corresponding to about 500 g (two 8-oz. glasses). Data were recalculated with dairy foods as the comparison based on a 32-year follow-up in 131,342 males and females.

The conclusion from these data indicates that increases in animal-based protein sources in the diet, compared to dietary plant-based protein sources, increases all-cause mortality risk.

The conclusion from these data indicates that increases in animal-based protein sources in the diet, compared to dietary plant-based protein sources, increases all-cause mortality risk.

Conclusions

The overall evidence for adults does not support high dairy consumption to reduce fractures. Current recommendations to increase dairy food consumption to three or more milk servings per day appears unjustified. Optimal intake of milk for any individual, of course, depends on overall diet quality. If diet quality is low, especially for children in low-income environments, dairy foods can improve nutrition. In contrast, where diet quality is high, as often observed in the U.S., increased dairy intake is unlikely to provide substantial benefits. Harm is actually possible.

When consumption of milk is low, the two nutrients of primary concern, calcium and vitamin D, can be obtained from other foods (or supplements) without the potential negative consequences of excessive dairy intake. Rich sources of calcium include kale, broccoli, tofu, nuts, beans, and fortified orange juice; for vitamin D, supplements can provide adequate intake at a far lower cost than fortified milk.

References

- Agnieszka Bzikowska-Jura, Aneta, et al. “The concentration of omega-3 fatty acids in human milk is related to their habitual but not current intake.” Nutrients 2019; 11:1585.

- Aleksandra Wesolowska, et al. “Lipid profile, lipase bioactivity, and lipophilic antioxidant content in high pressure processed human donor milk.” Nutrients 2019; 11:1972.

- Barr, S.I., et al. “Effects of increased consumption of fluid milk on energy and nutrient intake, body weight, and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy older adults.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2000; 100:810.

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., et al. “Calcium intake and hip fracture risk in men and women: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007; 86:1780.

- Fernández, M., et al. “Impact on human health of microorganisms present in fermented dairy products: an overview.” BioMed Research International 2015; 2015:412714.

- Ganmaa, D., Sato, A. “The possible role of female sex hormones in milk from pregnant cows in the development of breast, ovarian, and corpus uteri cancers.” Medical Hypotheses 2005; 65:1028.

- Harrison, S., et al. “Does milk intake promote prostate cancer initiation or progression via effects on insulin-like growth factors (IGFs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Cancer Causes Control 2017; 28:497.

- Hegsted, D.M., et al. “A study of the minimum calcium requirements of adult men.” The Journal of Nutrition 1952; 46:181.

- Olsen, S.F., et al. “Milk consumption during pregnancy is associated with increased infant size at birth: Prospective cohort study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007; 86:1104.

- Song, M., et al. “Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality.” JAMA Internal Medicine 2016; 176:1453.

- Willett, W., et al. “Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems.” Lancet 2019; 393:447.

- Willett, W.C., et al. “Milk and health.” New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382:644.

John Sapia - MPH - 68

Recommend that any future articles on milk explain that 8 oz.milk is equal to ? oz of cheese, yogurt etc. Therefore, If one consumes ? oz of cheese and/or yogurt etc. daily, with or without milk, they may be consuming equal to or more than the average adult serving of 1.6 vs 3 servings.

Reply

Vic Katch

In the table, it shows that 37 grams of cheddar cheese equals about 8 oz. of milk.

Reply

Ethel Larsen - 1972

Interesting that among the nordic countries, Finland (my ancestral homeland) has significantly lower fracture incidence despite greater milk product consumption, but is relatively similar to its neighbor to the east, Russia.

Reply

Russell Lyons - 1983

“This amount is substantially higher than the current average adult intake of only 1.6 calcium servings daily.” What is a calcium serving?

Reply

Linda Formsma Gottlieb - 46

Excellent explanation. Thank you.

Reply

doris shapardanis - 1972, Masters: l1977

Interesting information, especially for me…and older person!! It is good to consider and follow some of the resutls of this study.

Reply

Will White - PhD Nuclear Engineering, 2006

I note that the first graph (hip fracture rates) purports to show a trend (a helpful line is even included), but the data looks more like a random scatter. The lack of error bars (in either direction) may be an indication that the reference is unwilling to disclose the absence of any actual correlation. Disappointing, but not unexpected in a general interest article like this. I would caution the author that the subject is interesting enough without finding it necessary to exaggerate. Caveat lector.

Reply