A family’s quest for a hero’s ‘war chest’

From undisclosed honors to covert operations, the valiant military exploits of Colonel Kenneth Kreps were veiled in secrecy until a fateful discovery by his descendants. Witness the unveiling of a World War II hero’s saga as his family unpacks a long-lost treasure trove of historic memorabilia.

-

Lloyd Carr retires as associate athletic director

Former University of Michigan football coach Lloyd Carr retired as associate athletic director for the Wolverines.

-

Sheri Fink's deep reporting

She won a Pulitzer Prize for uncovering tragic events at a New Orleans hospital following Hurricane Katrina, but that was just one small part of a remarkable career.

-

Maker of heroes

How Dwayne McDuffie created some of the comics’ first black superheroes, invented the first heroic clean-up crew, and keeps kids TV icon Ben 10 in business.

-

What Division Street divided

Video: The true story of Ann Arbor’s dry line, and the rowdy, brawling student behavior it totally failed to prevent.

-

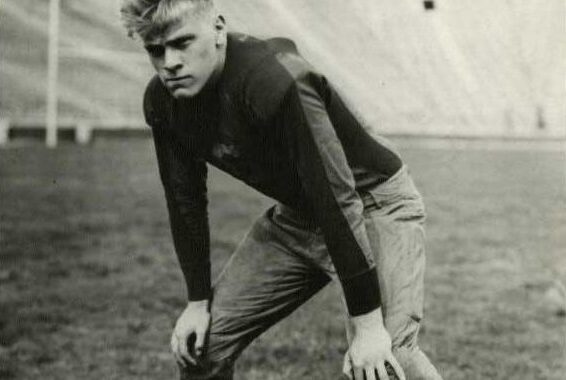

The innovator

How U-M coach Fritz Crisler and World War Two created modern football.

Plus: Lloyd Carr retires as associate athletic director -

Lowest resident undergraduate tuition increase in a quarter century

U-M will implement the lowest resident undergraduate tuition increase since 1984 paired with a record amount of undergraduate financial aid and a new Economic Hardship Program designed to offer additional help to Michigan families.

Related:

Columns

-

President's Message

Eureka! A look at the knowledge ecosystem

With $1.86 billion in research funding, U-M is leading the way in everything from energy solutions to artificial intelligence. -

Editor's Blog

A crisis by any other name…

You know what they say about opportunity. It knocks but once before the door slams shut. -

Health Yourself

So much for farm to table … We’ve got lab to table now

Who's ready to eat chicken that scientists 'hatched' in a lab and not from an egg? -

Climate Blue

How to keep your head above uncharted waters

Ricky Rood says goodbye to Floodtown as he guides us through the changing climate.

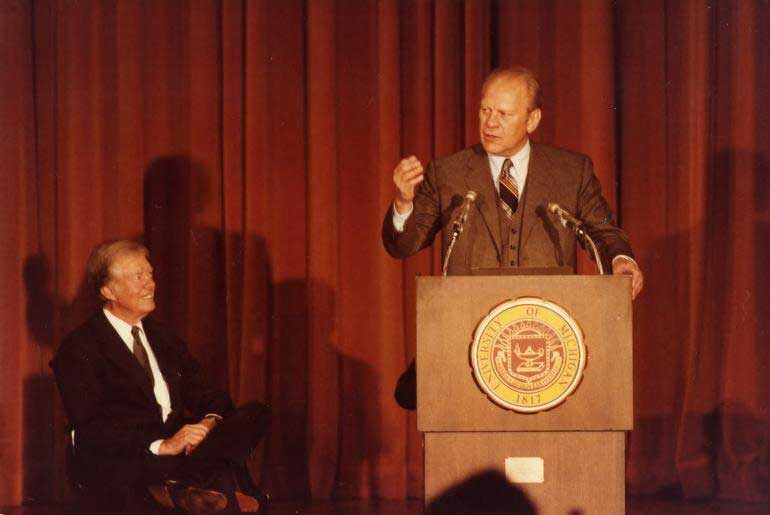

Commemorating an exceptional presidency

Fifty years ago, at a time of great division and turbulence in the U.S., Gerald R. Ford was sworn in as the 38th president of the United States. President Ford’s legacy is very much alive at the Ford School of Public Policy. This slideshow is inspired by the school’s recent tribute, “A life of public service,” in the Spring 2024 issue of State & Hill magazine. As noted by the editors, the values that distinguished Ford remain highly relevant to policy students today: his lifelong commitment to principled public service, his integrity, and his ability to connect across differences to forge consensus.