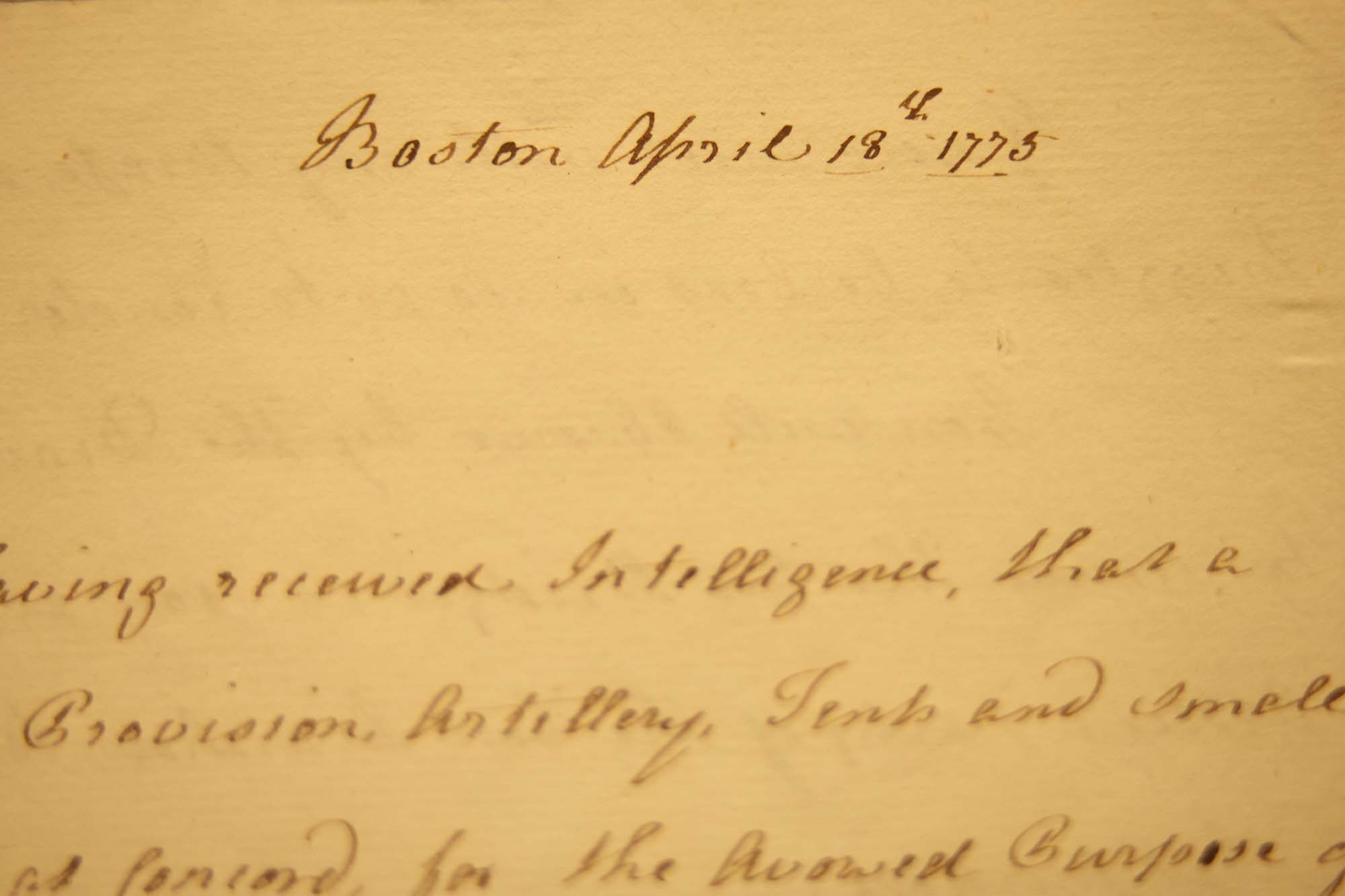

The order that launched the Revolutionary War, 250 years later

The ‘shot heard ’round the world’ can be traced to one manuscript containing the orders for the Concord Expedition on April 18, 1775. The quill-to-paper draft orders, penned by British Army officer Thomas Gage, sparked the Battle at Lexington and Concord the following day. U-M’s Clements Library holds the document.

-

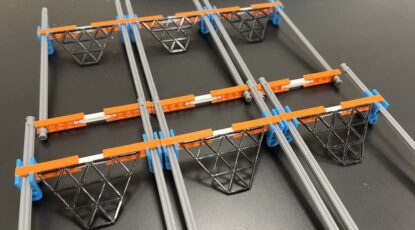

Not so simple machines: Cracking the code for materials that can learn

It’s easy to think that machine learning is a completely digital phenomenon, made possible by computers and algorithms that can mimic brain-like behaviors. But the first machines were analog and now, a small but growing body of research is showing that mechanical systems are capable of learning, too, say physicists at U-M.

-

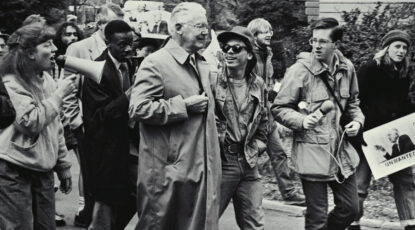

Who was Robben Fleming?

U-M Regent Philip Power once remarked that Robben Fleming, U-M president from 1968-78, viewed clashes as the engine of progress. Power wasn’t wrong. Fleming’s background in labor law prepared him for the tumultuous decade when student protest and anti-war sentiment captivated the campus.

-

Dental alumni discover they have more than Michigan in common: They are siblings

This brother and sister went through the U-M dental school one year apart but never knew about each other until 30 years later. Today, they enjoy a newly expanded network of relatives, friends, and of course, Michigan alumni.

-

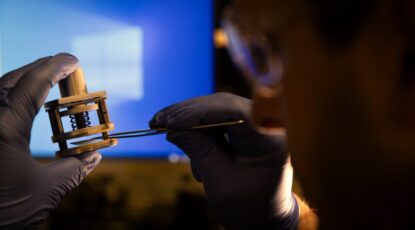

‘Unprecedented’ level of control allows person without use of limbs to operate virtual quadcopter

A brain-computer interface, surgically placed in a research participant with paralysis in all four limbs, provided him an unprecedented level of control over a virtual quadcopter — just by thinking about moving his unresponsive fingers. Such groundbreaking technology could impact one’s ability to socialize, work, and enjoy recreational activities.

-

New water purification technology helps turn seawater into drinking water without tons of chemicals

Cutting acid and base treatments from conventional desalination plants could save billions of dollars globally, making seawater a more affordable option for drinking water, say experts at U-M. A study describing the new technology has been published in Nature Water by engineers at Michigan and Rice University.

-

The Breakey Boys: A dynasty of doctors

Over 166 years, five successive generations of Michigan-minted doctors have left their collective mark on medicine — and the Breakey family. The birth of the Breakey dynasty of doctors coincides closely with the birth of the University of Michigan Medical School, which opened 175 years ago. That’s James Fleming Breakey, MD 1894, on the far right.

Columns

-

President's Message

Reaffirming our focus on student access and opportunity

U-M seeks to ensure every student will rise, achieve, and fulfill their dreams. -

Editor's Blog

Peace out

It's a mad, mad, mad, mad world out there. -

Climate Blue

Keeping our focus on climate

As federal support for climate science wanes, Ricky Rood remains hopeful. -

Health Yourself

Are you an ‘ager’ or a ‘youther’?

Why do some people appear younger or older than people born in the same year?

Listen & Subscribe

-

MGo Blue podcasts

Explore the Michigan Athletics series "In the Trenches," "On the Block," and "Conqu'ring Heroes." -

Michigan Ross Podcasts

Check out the series "Business and Society," "Business Beyond Usual," "Working for the Weekend," and "Down to Business." -

Michigan Medicine Podcasts

Hear audio series, news, and stories about the future of health care.

In the news

- USA Today US consumer sentiment and expectations fall again in April as tariff uncertainty continues

- CNN Beyond Ivy League, RFK Jr.'s NIH slashed science funding across states that backed Trump

- Detroit Free Press Inflation is slowing. Wages are up. So why does life feel costly for many Michiganders?

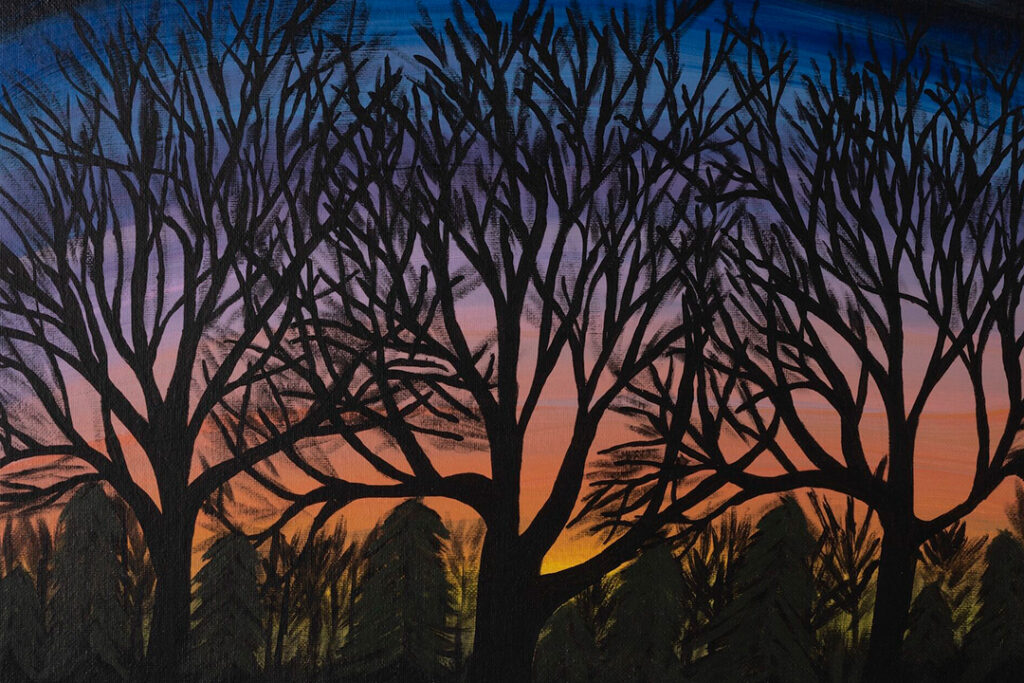

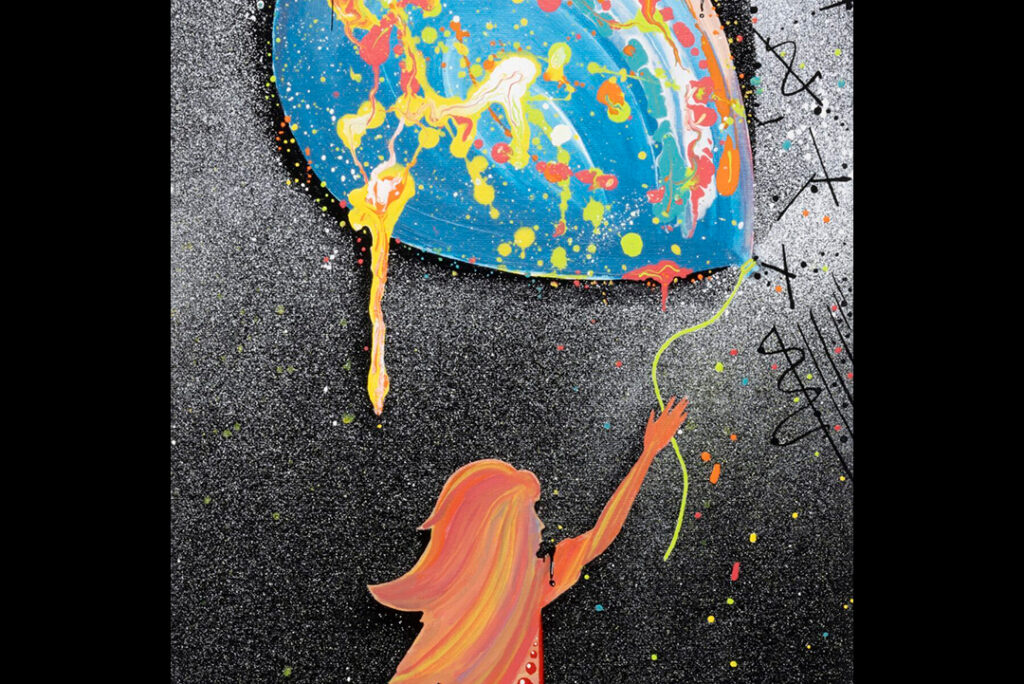

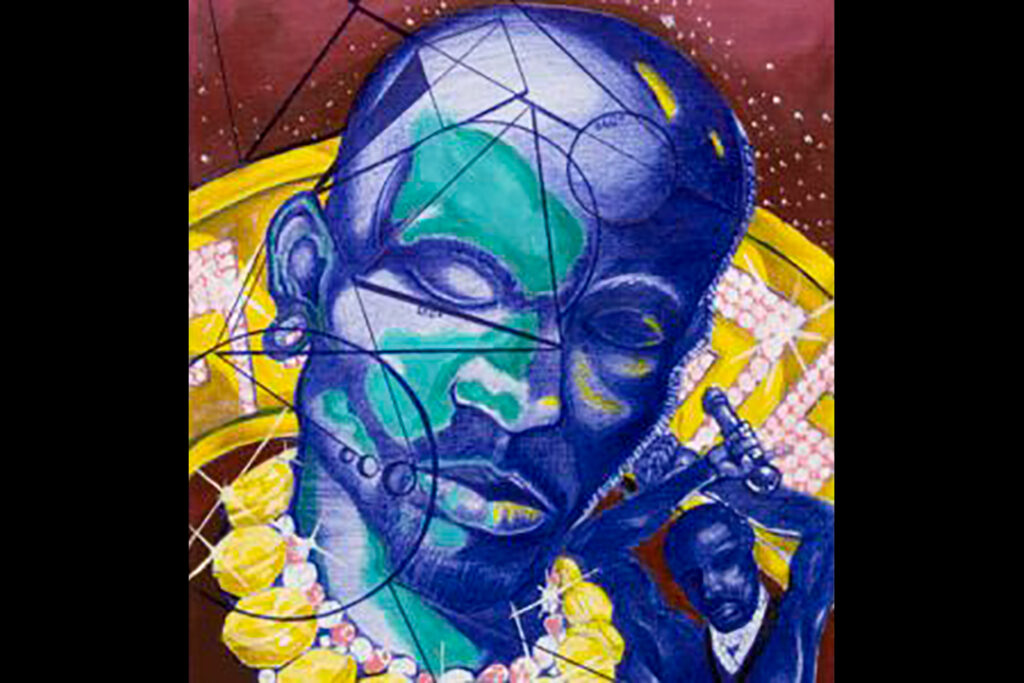

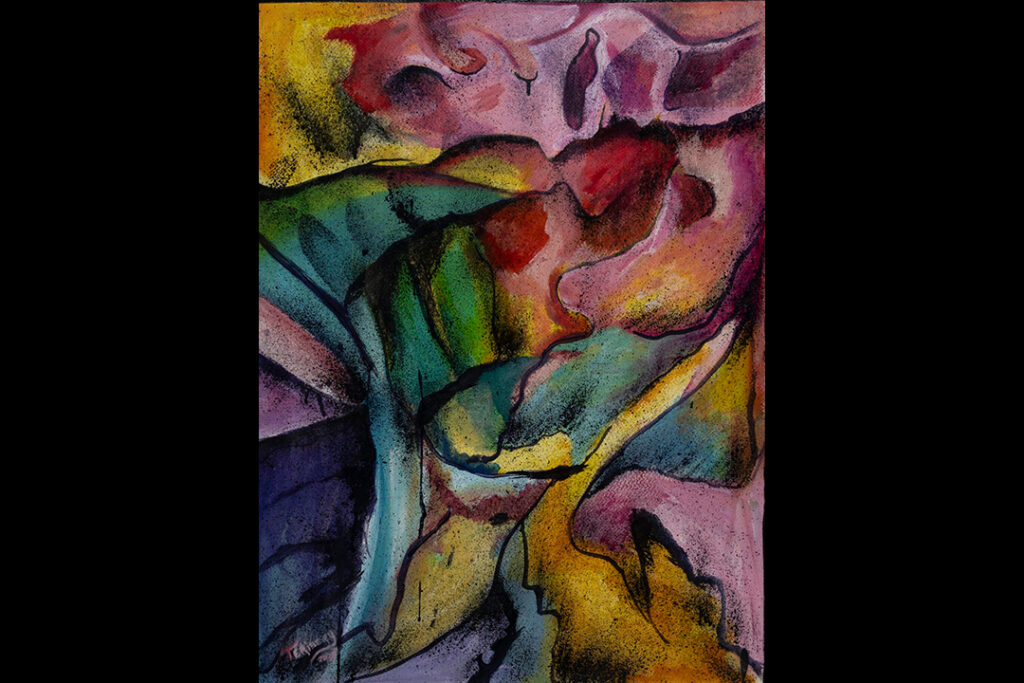

Creativity and connection across prison walls

One of the world’s largest and longest-running exhibitions of incarcerated artists is back with new programming designed to foster connection and deepen public understanding of incarceration in Michigan. The 29th annual Exhibition of Artists in Michigan Prisons, curated by U-M’s Prison Creative Arts Project, showcases 772 artworks by 538 artists incarcerated in 26 state prisons. The Duderstadt Center Gallery on U-M’s North Campus is presenting the artwork through April 1.