Back in the day

Some 3,000 years ago, medical “specialists” began to emerge in Egypt. These experts studied different body parts and physical functions, such as circulation, breathing, sleeping, and muscle function. They also focused on “general hygiene,” which at the time referred to maintaining health and preventing disease through cleanliness.

In ancient Egypt, the richest citizens employed “guardians of the royal bowel movement,” a title translated from the hieroglyphics to mean “Shepherd of the Anus.”

As these early physicians sought to identify and control factors linked to disease development, they focused on water and food quality, sexual hygiene, feces removal, and other factors tied to public health. Eventually, they traced many diseases to the Nile River, which supplied the population’s drinking and bathing water. The river abounded with parasites that caused common digestive diseases, particularly constipation and diarrhea, and hemorrhoids.

Therefore it was not surprising that the hygiene field flourished during this time period. In fact, the richest citizens employed special physicians known as “guardians of the royal bowel movement,” a title translated from the hieroglyphics to mean “Shepherd of the Anus.”

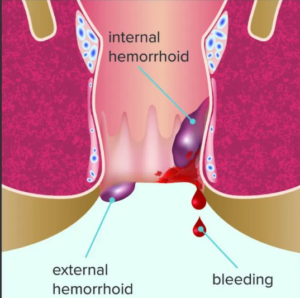

For this piece, I am going to shepherd you through the causes and treatments for the unpleasant condition of hemorrhoids, which are swollen and inflamed veins around the anus or in the lower rectum. There are two hemorrhoids types, also called piles:

- External hemorrhoids form under the skin around the anus

- Internal hemorrhoids form in the lining around the anus and lower rectum

Prevalence/causes

This uncomfortable condition arises in both men and women, affecting about one in 20 Americans. About half of all adults older than age 50 experience hemorrhoids regularly. They are more likely to develop in individuals who:

- Strain during bowel movements

- Sit on the toilet for long time periods

- Experience chronic constipation

- Consume low-fiber foods

- Are older than age 50

- Are overweight

- Have weakened supporting tissues in the anus and rectum (which commonly occurs with aging and pregnancy)

- Frequently lift heavy objects

Complications

Be careful, because complications can arise, including:

- Blood clots in an external hemorrhoid

- Skin tags — extra skin left behind when an external hemorrhoid blood clot dissolves

- External infections

- Strangulated hemorrhoid — when the muscles around the anus cut off the blood supply to an internal hemorrhoid that has fallen through the anal opening

- Anemia

Symptoms

External hemorrhoids’ major symptoms include itching, one or more hard, tender lumps, and pain, especially when sitting. For most people, these symptoms subside within a few days.

Rectal bleeding represents the most common internal hemorrhoid symptom, most often involving bright red blood in the stool, on toilet paper, or in the toilet bowl after a bowel movement. A secondary symptom is prolapse — when a hemorrhoid falls through the anal opening causing pain and discomfort.

Diagnosis

Your doctor may choose a variety of methods for diagnosis, including:

Your doctor may choose a variety of methods for diagnosis, including:

- Detailed GI medical history

- Physical exam for external hemorrhoids

- Digital rectal exam

- Anoscopy: A lubricated plastic tube called an anoscope (a device fitted with a magnifier and a light) inserts a few inches into the rectum allowing for examination of the inner lining.

- Sigmoidoscopy: A sigmoidoscope (lighted tube with a camera) inserts in the lower colon and rectum to view the inside for any abnormalities.

Treatment Options

Basic (simple) home treatments include the following:

- Warm bath (sitz bath) — Sitting in three inches of warm (not hot) water for 15 minutes or so, several times per day to help reduce swelling.

- Ointments — Applying small amounts of petroleum jelly or other over-the-counter creams or ointments made for hemorrhoid symptoms.

- A 1% hydrocortisone cream on the skin outside the anus also can relieve itching.

- Witch Hazel — This natural anti-inflammatory, applied to the inflamed area, can reduce swelling and itching.

- Soothing wipes — Cleaning the area with a gentle baby wipe, a wet cloth, or a medicated pad often helps.

- Cold compress — Applying a simple cold pack on the tender area for a few minutes can bring down swelling and stop itching.

- Diet — Eat more high-fiber foods (fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains). Females should consume a minimum 25g of high-quality fiber per day; men should consume a minimum 35g of fiber per day.

- Exercise — Light-to-moderate physical activity (not vigorous) has been shown to promote regular bowel movements and thereby reduce hemorrhoid onset and incidence.

- Stool softeners — These products often prove helpful if a high-fiber diet fails to work.

- Hydration — Drink at least a half-gallon of liquid per day.

Advanced treatment

If one doesn’t experience improvement after a week of home treatments, it may be necessary to see an appropriate healthcare provider for advanced treatment solutions. These may include the following:

- Rubber band ligation: A small rubber band placed around the base of a hemorrhoid cuts off blood supply to the vein.

- Electrocoagulation: An electric current stops blood flow to a hemorrhoid.

- Infrared coagulation: A small probe inserted into the rectum transmits heat to rid the hemorrhoid.

- Sclerotherapy: A chemical injected into the swollen vein destroys the tissue.

Surgical treatments include:

- Hemorrhoidectomy: Surgery removes large external hemorrhoids or prolapsed internal ones.

- Hemorrhoid stapling: A stapling instrument removes an internal hemorrhoid, or it pulls a prolapsed internal hemorrhoid back inside the anus to hold it there.

Diet as a treatment: What works?

The most effective way to prevent hemorrhoids is to avoid constipation by consuming a high-fiber diet. Fiber adds bulk to the diet and thereby promotes intestinal food transit.

Simply adding more fiber-rich foods represents the best way to avoid constipation, the leading cause for hemorrhoid development. Nearly 60 million Americans suffer from chronic constipation — particularly a problem in women and the elderly.

Two interesting studies looked at the best food(s) or supplements to encourage frequent and full bowel movements while reducing constipation and hemorrhoid development.

A plant-based diet can help make you regular and avoid hemorrhoids, among other beneficial changes, says Katch.

One study assessed the bowel function of 51 subjects who habitually consumed an omnivorous, vegetarian, or vegan diet. The subjects on these diets had a mean fiber intake equal to 23g, 37g, and 47g, respectively. Results indicated that plant-based eaters had a greater defecation frequency and passed softer stools. All bowel function measurements were significantly correlated with total dietary fiber intake. As dietary fiber increased, mean stool transit time decreased, stool frequency increased, and the stools became softer.

In another study, researchers performed a randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of dried plums (prunes) to psyllium (Metamucil) on bowel-movement frequency, completeness, and consistency. Subjects were first tested on their regular diet. Then, they were introduced to psyllium (11g with 8 oz. of water twice per day), or 50g of prunes (5-8 prunes) twice per day for three weeks.

Subjects maintained daily symptom diaries. After the first treatment period, subjects discontinued all therapy for a one-week washout period. Subsequently, subjects were crossed over to receive either dried prunes or psyllium for an additional three-week treatment period. After study completion, subjects were asked to continue with their usual remedies for constipation, and return for a follow-up visit at six weeks.

Results showed that on their normal diet, subjects averaged about 1.7 bowel movements per week, with about 20 percent of the subjects having less than one bowel movement per week. (Is this even possible?) Subjects increased their bowel frequency to an average 3.5 movements per week on prunes. That’s about a bowel movement every other day, or so. After prune cessation for a week, the subjects’ bowel frequency returned to the 1.7 times per week. After consuming psyllium for three weeks, the subjects increased bowel frequency to 2.8 times per week. Again, bowel frequency returned to baseline after returning to their regular diet. These data clearly indicate that introducing plant-based food (i.e., fiber) increased bowel frequency significantly.

Bottom line

If you’re constipated, with hemorrhoids, try a plant-based diet. It will help make you regular, among other beneficial changes. I’ve discussed the positive effects of plant-based eating in the following Health Yourself articles:

So, what would happen if a person consistently ate a plant-based diet all the time? Not surprisingly, plant-based eaters report an average bowel frequency about 10 times per week, and no constipation or hemorrhoids.

References

- Attaluri, A., et al. “Randomised clinical trial: Dried plums (prunes) vs. Psyllium for constipation.” Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2011;33(7):822.

- Bassotti, G., et al. “Colonic motility in man: features in normal subjects and in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation.” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 1999;94(7):1760.

- Bharucha, A.E., et al. “Insights into normal and disordered bowel habits from bowel diaries.” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2008;103(3):692.

- Chen, T.S., Chen, P.S. “Gastroenterology in ancient Egypt.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1991;13(2):182.

- Christensen, J. “The response of the colon to eating.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;42(5 Suppl):1025.

- Davies, G.J., et al. “Bowel function measurements of individuals with different eating patterns.” Gut. 1986 Feb;27(2):164-9.

- Hemorrhoids. MedlinePlus website. Accessed February 2023.

- Jenkins, D.J., et al. “Effect of a very-high-fiber vegetable, fruit, and nut diet on serum lipids and colonic function.” Metabolism. 2001;50(4):494.

- Maksimović J., Maksimović, M. “From history of proctology.” Arch Oncology. 2013;21(1):28.

- Sanjoaquin, M.A., et al. “Nutrition and lifestyle in relation to bowel movement frequency: A cross sectional study of 20,630 men and women in EPIC-Oxford.” Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7(1):77.

- Sullivan, R. “A brief journey into medical care and disease in ancient Egypt.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1995 Mar;88(3):141.

- Trowell, H. “The development of the concept of dietary fiber in human nutrition.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1978;31(10 Suppl):S3-S11.

- Tucker, D.M., et al. “Dietary fiber and personality factors as determinants of stool output.” Gastroenterology. 1981;81(5):879.

- Walker, A.R., Segal, I. “Dietary fiber, bowel behavior, and constipation.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1990;12(4):478.

- Walter, S.A., et al. “Assessment of normal bowel habits in the general adult population: The Popcol study.” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45(5):556.

(Lead image: iStock.)

John C. John C

Thorough article and well written. Thank you for the education!

Reply